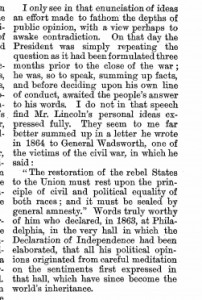

One of the most unusual documents in the Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (Roy Basler, ed) is an excerpt of a letter allegedly written in 1864 by Lincoln to Gen. James S. Wadsworth. The document seems to reveal Lincoln’s support for universal black suffrage while also hinting at elements of an egalitarian turn in his racial views. It contains what is arguably the most liberal racial viewpoint to be found in any of Lincoln’s writings: “The restoration of the Rebel States to the Union must rest upon the principle of civil and political equality of the both races.” This is significant in itself because Lincoln’s other known writings on this subject – in particular his famous private letter to Louisiana Gov. Michael Hahn – reveal a significantly more tepid and limited endorsement of black suffrage at most, making the Wadsworth Letter the most far-reaching endorsement to purportedly come from Lincoln’s hand.

I note purportedly though because its provenance is highly problematic.

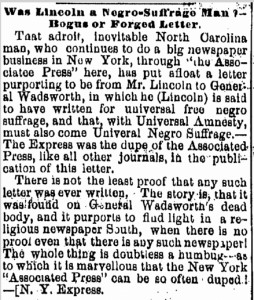

The letter itself is incomplete, consisting of only four paragraphs from what purports to be a a longer document. No original copy of the letter survives, and its verified existence dates no earlier than September 25, 1865 when its text appeared in the New York Tribune some five months after Lincoln’s death. The Tribune claimed to have obtained it from a September 18, 1865 issue of a newspaper called the Southern Advocate, though no such issue has ever been found and the paper itself may not have ever existed.

As Ludwell H. Johnson has shown, the text used by Basler in the Collected Works is also flawed. The fourth paragraph where Lincoln extols the “principle of civil and political equality of the both races; and it must be sealed by general amnesty” is entirely suspect. It was appended to the first three by editors of a 1905 edition of Lincoln’s work, who acquired it from an article by the Marquis de Chambrun, a French diplomat who became an acquaintance of Lincoln in the last few weeks of his life.

The problem is that Chambrun’s passage was not a excerpt of the letter but an imperfect synopsis of the original three paragraphs from the New York Tribune in 1865. It was not published until 1893, and actually consists of a translation of a French-language essay that was found in Chambrun’s papers after his death. Absolutely nothing about the final paragraph is therefore valid, as it was not even an intended quote of Lincoln to begin with except for the posthumous insertions of an editor at Scribner’s Magazine.

These problems have not precluded other historians from using the Wadsworth Letter to frame arguments about Lincoln’s racial views. In an irony that will not be lost upon regular readers of this blog, Allen Guelzo even cited the Wadsworth Letter to “disprove” Lincoln’s late-life interest in black colonization while chastising Michael Lind for suggesting otherwise.

But what if the Wadsworth Letter is nothing more than a political forgery, as Johnson’s article suggests? The Wadsworth Letter appeared in print at a time when the martyred president’s name made him a popular ally to have, and the Tribune editor Horace Greeley readily enlisted it to support congressional Reconstruction causes (which to the radicals’ credit, did include what would eventually produce the 15th amendment)

Less noticed though equally significant, the Wadsworth Letter also had its doubters from the very moment it was published. Most of its early skeptics were motivated by overt racial animosity typified by an intense hostility to black suffrage, and should be read accordingly. But there was also reason to doubt the authenticity of the Tribune’s newly found endorsement from Lincoln.

The first piece of evidence came out in the papers a few days after the Wadsworth letter in the form of a competing letter by Duff Green that also seems to have escaped modern historical notice. Green, a longtime Washington newspaper editor who sided with the Confederacy and moved south during the war, was nonetheless related by marriage to Mary Todd Lincoln’s family and had been an acquaintance of Abe’s since renting him a house during his single term in Congress in 1848. Green was also in Richmond in April 1865 when Lincoln arrived to inspect the surrendered city, and owing to their old relationship, had a private audience with the president on board the USS Malvern as it was docked in the James River (some readers may note that a fanciful version of this encounter appears in the 1885 memoirs of Admiral David Dixon Porter, though it is likely a fabrication in its own right…but I’ll save that for another post).

Green provided an account of his conversation with Lincoln in a letter to the New York World on September 26, 1865, a few days after the Wadsworth letter appeared and with the express intention of rebutting the claim that Lincoln “pledged himself to require a qualified negro suffrage as a condition of general amnesty.” This diverged from Green’s account of the conversation on the Malvern, where Lincoln reportedly offered no specific conditions of amnesty beyond the laying down of arms and the return of the southern states to the Union. “I have the pardoning power, and I will use it freely,” Lincoln reportedly said. Curiously on the matter of slavery, Green’s Lincoln hints that the southern states – upon return to the Union – would be free to vote against the 13th amendment, echoing an odd and controversial proposition that was reportedly made by William Seward a few months prior at the Hampton Roads conference. Green’s Lincoln does hold fast to emancipation though, noting “I cannot recall my proclamation.”

There may be plenty of reasons to question how accurately Green relayed this conversation, though it does carry some consistency with Lincoln’s letter to Gen. Godfrey Weitzel the same day (later rescinded following the surrender of Lee and intense opposition by Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton), allowing him to reconvene the Virginia legislature for the purpose of invalidating the secession ordinance. Green also clearly embellished the conversation in later versions to suggest a stronger ambivalence about the 13th Amendment (though, interestingly enough, he never suggests that Lincoln was ambivalent about the Emancipation Proclamation). But as a glimpse into the context of politics in September 1865, it is a telling indicator of an early battle over the claim to Lincoln’s name and legacy. The Wadsworth Letter and Green’s retort are both parts of that contested claim and in the Wadsworth Letter’s case, far more an indicator of immediate post-war politics than anything that could be reliably attributed to a private wartime document from Lincoln.

We may never know for certain the source of the Wadsworth Letter, though at this point the weight of the evidence points to a postwar embellishment or fabrication that was then inadvertently embellished further by the addition of the Chambrun passage upon its mistaken identification as an additional paragraph.