So it turns out that my earlier suspicions about possible academic integrity issues in Kevin M. Kruse’s scholarship were warranted. After finding hints of borrowed textual structures and word phrasing in a 2015 book by the Princeton historian, I decided to take a closer look at some of his other work. I turned to his 2005 book White Flight, which was the basis of Kruse’s essay in the 1619 Project. Another suspiciously-similar passage popped up in its opening chapter, which prompted me to check the dissertation that the book derived from. In short order, I discovered that Kruse appears to have plagiarized large blocks of text from two other books by scholars Ronald Bayor and Thomas Sugrue. The details are written up here in Reason.

The discoveries about Kruse’s dissertation came as a shock to the political activist wing of the history profession, where Kruse is a well-known social media star famous for his “Historian here…” twitter threads that purport to correct both real and imagined errors of fact and interpretation by conservative-leaning political commentators. Most conceded that the evidence looked very bad for Kruse, but more than a few of his online fans redirected their ire at me personally for having discovered the similarities. Unfortunately, their decision to “shoot the messenger” was expected. In today’s hyper-politicized academy, evidence is almost wholly subordinate to a far-left ideological narrative.

The same pattern played out a few years ago when I drew attention to a long list of serious historical errors and misrepresentations in Nancy MacLean’s book Democracy in Chains. True to form, several of the exact same parties that lashed out against me over MacLean’s book are now on the warpath over the plagiarism revelations about Kruse.

The most vocal Kruse defender at the moment is Lora Burnett, who formerly taught history at Collin College. I am not certain what type of history Burnett actually specializes in, because she’s never published a substantial work of research of any kind. But she tweets about politics. A lot.

During the sparring over MacLean’s book, Burnett attacked me personally on multiple occasions. It started around July 2017 when she took umbrage over a post I wrote for the History News Network. Anticipating similar false allegations by MacLean herself, Burnett became convinced that a bizarre conspiracy was afoot to destroy Democracy in Chains. She began flooding social media with tweets and blog posts, insinuating that the libertarian Koch Brothers had hired me to investigate and discredit MacLean’s work

The truth was much more simple. I maintain an active research interest in the work of economist James M. Buchanan, who was the primary target of MacLean’s book. I knew Buchanan briefly and met him a few times as a grad student at GMU in the mid-2000s, and I drew heavily on his work (along with his frequent collaborator Gordon Tullock) in my own dissertation. What I found in MacLean’s book was an ideologically motivated hatchet job. I detailed my findings in a lengthy (and, unlike MacLean’s book, peer-reviewed) article for the Southern Economic Journal, co-authored with Art Carden and Vincent Geloso. It places Democracy in Chains under a microscope and finds substantial evidence of factual error, misrepresentations of archival sources, and simply making up disparaging claims about Buchanan out of thin air.

Returning to Burnett though, she simply could not shake herself of the conspiracy theory that I was being financed by the Kochs to undertake this project. In reality, there was no “Koch money” to be found. I funded my part of the research out-of-pocket on a non-tenured professor’s salary while managing a 4-3 teaching load. That did not stop Burnett from plastering her conspiracy theory all over social media. In time, Burnett’s commentaries grew more fanciful, more conspiratorial, and more profane. It’s safe to say that if she addressed a professional colleague with a similar barrage of gratuitous sexism and vulgarity, Burnett’s behavior could easily be construed as creating a hostile and discriminatory workplace environment.

Perhaps expectedly, Burnett jumped into the Kruse controversy with a defense, masquerading as an objective analysis. It offers up a long list of excuses, including floating the farcical theory that early 2000s word processor technology “accidentally” converted several block-quoted passages into text and deleted the citations. It also launches into a political tirade, accusing me of being a “bad faith” actor for bringing evidence of the problems with Kruse’s work to light. But I want to call attention to the one claim by Burnett that appears to be getting some traction among other activism-inclined historians.

As part of her defense strategy for Kruse, she concedes that the plagiarized dissertation passages are real…and then promptly tries to minimize their severity by downplaying them as “only six sentences.”

This argument is untenable though because similar problems also appear in Kruse’s other works. As I documented in Reason, several passages from Kruse’s 2015 book One Nation Under God appear to be directly cribbed from other sources, showing nearly-identical phrasing and sentence structures. As with other famous plagiarism cases (think Stephen Ambrose and Doris Kearns Goodwin), Kruse did partially-cite these sources in his footnotes. But the problems arise from his presentation of nearly-identical words without the requisite quotation marks to signify that they came from another source.

So how does Burnett get around the issue with Kruse’s other works? Quite simply, she attempts to redefine the meaning of plagiarism to exclude the borrowing of texts in this fashion.

Burnett writes that “Kruse’s practice here, paraphrasing a government document and then citing it, is standard and careful historical practice.” She repeats this claim multiple times, responding that each example of Kruse’s textual cribbing is a perfectly permissible “paraphrase” and in fact constitutes “standard and responsible historical scholarship.” She then elaborates on the charge, taking a number of gratuitous swipes at me in the process:

It’s certainly possible that the author of the Reason piece does not understand standard and responsible historical scholarship and thus is unable to distinguish between unattributed paraphrase, attributed paraphrase, and word-for-word reproduction of a source without proper attribution (quotation marks or block-quoting of the text, and citation). It’s also possible that the author of the Reason piece is making a bad-faith argument and deliberately mischaracterizing Kruse’s work in these passages as an example of plagiarism in order to draw a false equivalency between Kruse’s writing and David Clarke’s writing, not so much to malign Kruse as to vindicate Clarke.

Keep in mind that although she claims to be speaking on behalf of her profession and its “standard and careful historical practice,” Burnett has an exceedingly slim record as a practicing historian. So what are we to make of Burnett’s new redefined concept of plagiarism?

Far from being “standard and careful historical practice,” Burnett’s attempts to euphemize textual lifting as innocent paraphrasing is at direct odds with how the American Historical Association defines plagiarism.

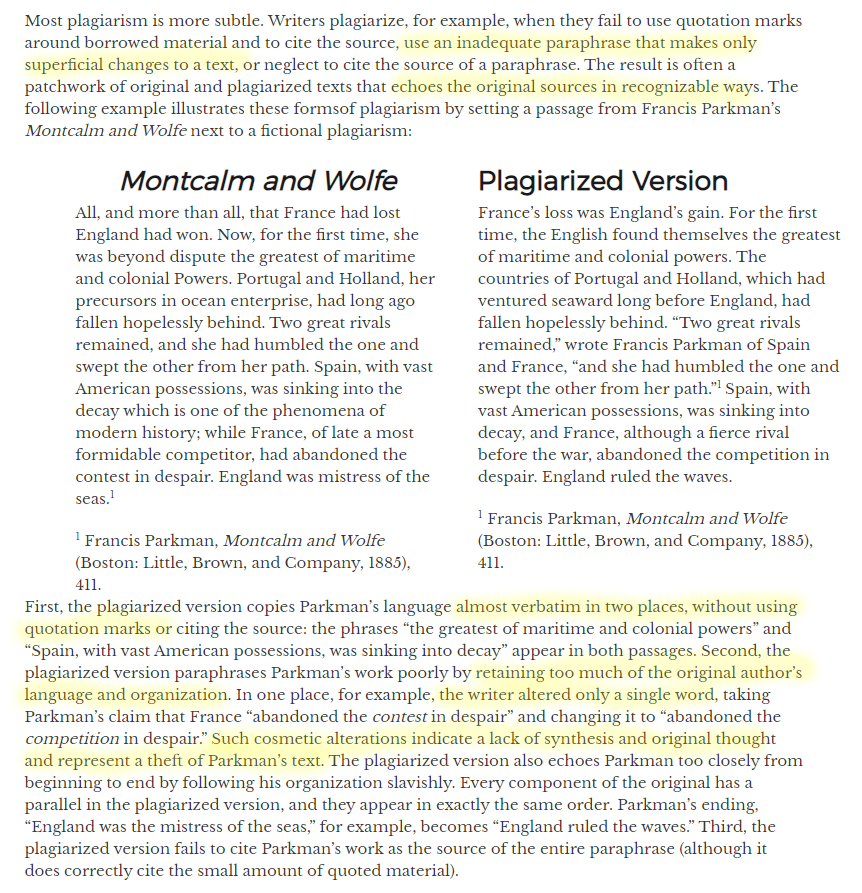

The image below comes from the AHA’s published guidelines on professional ethics. As the highlighted passages and in-text example make clear, the AHA clearly and unambiguously defines “inadequate paraphras[ing]” as plagiarism. Lifting phrases and sentences from original sources “in recognizable ways,” modifying only a couple of words in a borrowed sentence, and making what they call “cosmetic alterations” to a borrowed but un-quoted text are all serious lapses of scholarly standards – even when the lifted source is referenced in the footnotes. They even provide a convenient example that strongly resembles several of the discoveries in Kruse’s works. It too has a footnote citation, yet this does not exonerate the plagiarism example’s author from lifting lines of text without the requisite quotation marks.

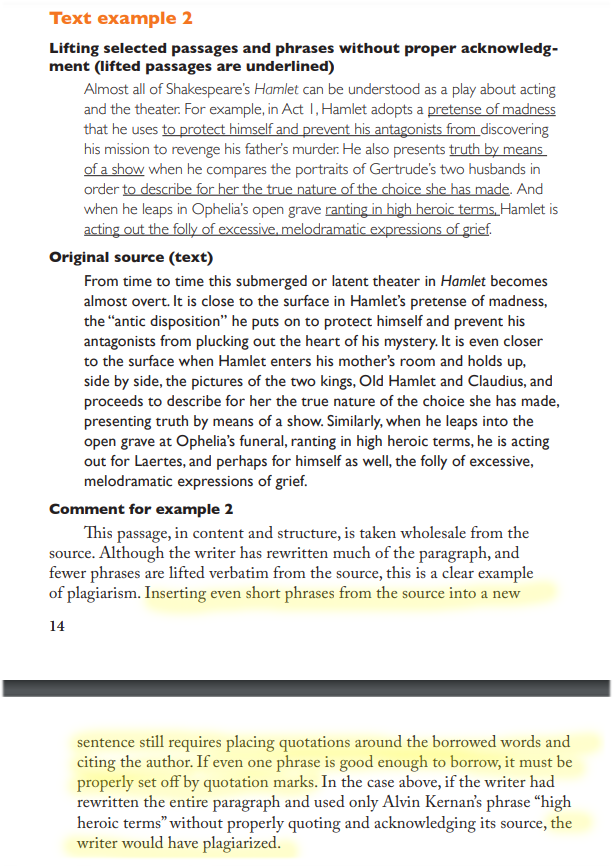

The AHA is not alone in reaching this judgment. Princeton University, where Kruse teaches, applies a similar standard in its academic integrity rulebook for students. At Princeton, closely similar texts that lift “even short phrases” without “placing quotations around the borrowed words” meet the university’s definition of plagiarism. In the example given by Princeton, even an improperly borrowed three-word phrase qualifies as plagiarism if it does not contain quotation marks.

It remains an open question as to whether Princeton will act in Kruse’s case, and – if so – what penalties they will consider. The guidelines above are also for students, although it stands to reason that faculty members should adhere to the same rules that they are tasked with enforcing in the classroom.

Nonetheless, both the AHA and Princeton definitions of plagiarism are significantly more strict than the one that Burnett seemingly invents in her latest blog post. It remains unclear whether this error derives from its convenience to Burnett’s political positions, or from her own unfamiliarity with standard and responsible practices of historical scholarship.