A little over a week ago I strongly criticized Judge Andrew Napolitano’s recent appearance on the Daily Show for his slipshod handling of Civil War history and for a couple of factual errors in his presentation about the Morrill Tariff. I was not the only critic, and others also seized upon Napolitano’s claim that Lincoln enforced the Fugitive Slave Act in “the South.”

This strikes me as more of an issue of inexact wording – “the South” and the CSA are usually used interchangeably in the context of Civil War discussions, although technically Lincoln did enforce the Fugitive Slave Act in the southern border states and the District of Columbia. In the larger scheme of things it was a minor point relative to the tariff, which is why I did not pursue it, though on that narrow sense Napolitano was in fact right.

James Oakes – one of Stewart’s panelists on the same segment – has continued to press the issue though in an article that appeared today on HNN. The relevant passage appears as follows:

“Perhaps I misunderstood Judge Napolitano’s point. When he insisted that he was talking specifically about Lincoln, that Lincoln “enforced” the Fugitive Slave Act, that he “used” federal marshals to enforce the law—I somehow thought Napolitano was suggesting that Lincoln personally ordered marshals to return fugitives—which Lincoln never did.”

Now Oakes is normally a thoughtful historian, even as I disagree with some of his interpretations on how aggressively and when Lincoln pressed his emancipation policy. But on this point of fact he is simply wrong. While Lincoln could hardly be described as a “slave hound” like some of his predecessors in the White House, he did in fact directly support the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act in at least one notable instance.

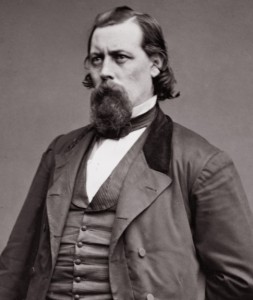

Lincoln’s appointed U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia was Ward Hill Lamon, a close personal friend from Illinois who briefly served as his junior law partner. Lamon’s job allowed him to double as Lincoln’s informal bodyguard and to carry out various personal and political tasks for the president throughout the war. In this sense he was something of a political consigliere to Lincoln, which is also the reason Lincoln gave him a position that kept him nearby.

When Lamon received his appointment as U.S. Marshal he also assumed custody of the D.C. jail, which was used as a holding place for escaped fugitive slaves. And since D.C. was within the slaveholding region of the country though it remained part of the Union during the war, Lamon continued to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act locally. His action was also entirely consistent with Lincoln’s public statements that the act would be enforced and – given Lamon’s close personal proximity to the president – it is unlikely that he would have continued to enforce it had it not been Lincoln’s desire.

(Note that this does not make Lincoln into some die-hard supporter of the Fugitive Slave Act, by the way – it only establishes that he continued it as a matter of law and policy in a region where the war had not yet disrupted the enforcement mechanisms of the southern slave economy).

In late 1861 Lamon’s action came under fire after some abolition-minded members of the U.S. Senate caught word that he was holding fugitive slaves from the District and possibly Maryland in the D.C. jail and began pressuring through congressional and military channels for their release. On December 9, 1861 the Senate issued a demand to Lamon to inform them by “what authority he receives slaves into the jail of the District at the request of their masters and holds them in confinement until discharged by their masters.” Lamon’s December 16 response affirmed his enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act and read in part:

“In obedience to the resolution of your Honorable body, a copy of which accompanies this, I have the honor to state that since I have held the office of Marshal of the District of Columbia, three persons claimed to be slaves, have been admitted into the jail of said District on the requests, respectively, of the persons claiming to be their owners; that this has been acquiesced in by me, upon an old and uniform custom here, based as I supposed upon some valid law, but of which supposed law I have made no investigation.”

What the Senate did not know at the time is that this carefully phrased answer had actually been drafted not by Lamon but by the president himself. It appears in Volume 5 of the Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, and the original scrap from Lincoln is currently housed at the Huntington Library in Pasadena.

Lamon’s enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act did not end there, and in the next two months he survived a legislative attempt to abolish his office as well as an effort by the abolitionist Gen. James S. Wadsworth to secure the release of the fugitives under the military authority. Lamon would later recount the Wadsworth incident in an unpublished manuscript, also at the Huntington Library:

“The matter was eventually laid before the President. He called to his aid his Attorney General, who gave a prompt but decisive opinion that the civil authority ranked in authority the military in the present state of things in the District of Columbia and gave the further opinion that the Military Governor’s conduct was misguided and unauthorized, however philanthropic may have been his purposes and intentions.”

The continued dispute between Lamon and the Senate later became the impetus for the D.C. Emancipation Act in April 1862. Lincoln had been hesitant to press forward on this act out of fear that it might alienate allies and impede the gradual emancipation initiatives he was pushing in other border slave states. But given the fugitive situation at the D.C. jail, Sen. Henry Wilson decided to push ahead with D.C. emancipation to press the president’s hand and thereby negate the Fugitive Slave Act’s continued enforcement.

In the grander scheme of things, the D.C. enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act amounted to a relatively minor incident. The Union also largely negated the policy in the Confederate states by adopting an official policy of declaring escaped fugitive slaves to be “contrabands of war” and therefore no longer subject to return or enforcement. But in the case of his friend Marshal Lamon, Lincoln did indeed directly support enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act in the District of Columbia until an action of Congress rendered it moot to do so any further.