One of the most common narratives of the higher education literature is the claimed decline of the humanities. We are constantly told that the humanities are “under assault” in an academy that increasingly values the STEM disciplines and professional degrees over a “well rounded education.” The humanities are often cast as the victims of an allegedly “corporatized” university system (itself a bizarre and empirically nonsensical charge that unintentionally veers into the territory of Tim Robbins’ speech from Team America). Fields like literature, history, philosophy and the sort are portrayed as “undervalued” on account of their declining numbers of majors, poor job markets, and a proclivity to produce research that isn’t economically or scientifically trendy.

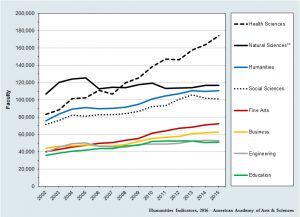

The narrative is so frequently repeated that most academics simply assume it is true without conducting any further investigation. Despite this widespread perception, it is also at odds with empirical reality. Earlier this summer the American Academy of Arts and Sciences released the latest statistics on the distribution of faculty across a range of academic fields. Their results show that humanities faculty numbers have consistently increased since the early 2000s. The following chart reflects the distribution of faculty at 4-year colleges and universities:

The humanities added almost 35,000 faculty to their ranks at 4-year colleges since 2002. They also outnumber almost every other field in the academy, with only two exceptions. The first is health sciences, which is something of an outlier due to numbers that are inflated by professional degree programs in nursing and medical care. The second is the natural sciences, which slightly outnumber humanities faculty at the present although they have shown almost no growth in the past 15 years.

Similar patterns may be seen at two year colleges, where humanities faculty added almost 60,000 members to their ranks. At both types of institutions, the humanities retain a sizable and growing presence on campus despite a mistaken conventional wisdom that loudly proclaims otherwise.

A closer examination of the humanities footprint reveals what is perhaps an even more surprising feature. Humanities faculty ranks are overwhelmingly dominated by the so-called MLA departments – English and foreign language literature. While the MLA fields are frequently portrayed as severely beleaguered, the numbers tell the opposite story. English alone employs almost twice as many faculty as the next closest humanities discipline (history), and the full MLA category makes up almost 50% of all humanities faculty.

MLA departments do use adjunct faculty at higher rates than the other humanities as well as the rest of the university system. But this appears to be a byproduct of their already-outsized and growing presence on campus, not any actual decline. English and foreign language departments are adding adjunct-taught classes to supplement their already-vast course offerings, the most prominent of which is the ubiquitous Freshman Composition 101. Often a mandatory feature of the general education curriculum for undergraduates, Composition 101 is the single most frequently taken college class in America. No other course even comes close, whether it’s in the humanities or any other discipline. Comparable introductory or remedial math courses, for example, are taken at less than half the frequency as composition.

So what explains the disparity between the rhetoric of the embattled humanities and an empirical reality that shows nothing of the sort? I suspect it traces back to the academic job market saturation in these fields. The humanities and the MLA disciplines in particular tend to produce new PhDs (and master’s degrees) at rates far in excess of the number of new job openings, and have done so for many decades. Even though the humanities are actually expanding at rates that equal or exceed almost every other field in the university system, they are still unable to supply enough faculty openings to meet the number of applicants who desire these same positions. This situation breeds the perception that the humanities are losing ground to other fields with healthier academic job markets, even though it is empirically false. Rather, their problem is a largely self-inflicted outcome of many decades of advanced degree overproduction that is strangely specific to a small number of heavily represented academic disciplines with a large and growing curricular presence on campus.