It is rare to see a discussion of civil war causality that does not turn at some point to the “secession declarations” of Mississippi, Georgia, Texas, and South Carolina. These statements from four of the original seven “deep south” states that created the Confederacy are among the most visible articulations of the pro-slavery cause from the Civil War era and leave little doubt about the deep attachment between that institution and the objectives of secession.

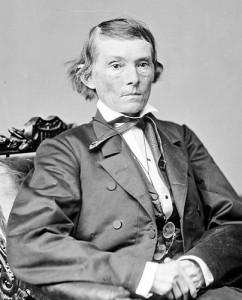

For all the familiar references to them, the conversation about these and other secession documents seldom extends beyond pointing out their pro-slavery character on the most superficial level. They seldom probe further into what these documents specifically said about the state of slavery and the threats to its continuance, and almost never attempt to examine whether their authors realistically assessed the political landscape of the incoming Lincoln administration. This latter consideration is telling, as no less a source than Alexander Stephens – the future Vice President of the Confederacy and himself an oft-cited exemplar of the pro-slavery cause – actually spent much of the secession winter arguing that the institution of slavery was safer inside of the union than outside of its constitutional protections. If Stephens was right – and the hindsight of the war-induced Emancipation Proclamation suggests he likely was on that specific question, at least for the short term duration of slavery – then why did the secessionists take the gamble of disunion in the name of protecting slavery?

In the short article at the link below, I endeavor to answer that question by looking at the secession declarations in depth and approaching the deep south’s departure as a Hirschman exit that was intended to recover and reassert government support and subsidy for the maintenance and continuation of slavery. The secessionists heavily emphasized the non-enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act and a litany of complaints about “insurrectionist” abolitionist activities in the wake of the John Brown raid as causes for their departure – both issues that are consistent with the realization that the political support for subsidizing slavery via federal and state enforcement was imperiled by the 1860 election, even as the legal continuation of slavery itself – as Stephens had argued – was not. While the territorial question also loomed behind the secessionist cause, it is interesting to consider that the act of seceding – the “exit” in this case – might also be interpreted as a de facto forfeiture of the prior western territorial claims that were ostensibly the cause of so much tension in the 1850s. This suggests the Confederates were likely looking elsewhere for expansion, unchained from anti-slavery elements in the northern government, and points to the real significance of “bleeding Kansas” being its relation to the political balance in the U.S. Senate, or at least more so than theories linking the economic viability of slavery to its continued territorial expansion.

In interpreting these events, the Public Choice interpretation of slavery offered by the late Gordon Tullock, as well as the political economy argument of Jeffrey Rogers Hummel relating to the public costs of enforcing the slave system weigh heavily upon the meaning of the secession declarations. I conclude in noting that while the Lincoln/Republican electoral threat to slavery itself is often severely overstated, the secessionists were more concerned with the specific weakening of the government benefits that slavery had thus far received. The exit that followed was not an attempt to save slavery from its impending abolition, but rather to shore up its rapidly diminishing political subsidy at the national level in the form of a new government that was unmistakably in the capture of slave-holding economic interests.