For more than a decade, University of Illinois-Chicago Professor Richard Jensen has been peddling a very strange historical thesis with a surprising amount of success in academic journals. Jensen argues that the “No Irish Need Apply” slogan – the infamous discriminatory display against Irish immigrants to the United States in the 19th century – is largely a myth. He contends that the slogan, referred to as “NINA,” is a case of projected self-victimization that Irish communities enlisted to evoke sympathy or encourage immigrant solidarity, while also suggesting that evidence of NINA’s actual use was exceedingly rare.

There’s a major problem with the Jensen/NINA thesis though: it’s complete bunk.

And the person who refuted Jensen’s claims is a high school student named Rebecca Fried. As detailed in this article, Fried investigated Jensen’s claims by scanning several online newspaper databases and finding extensive evidence of the nativist NINA slogan in hundreds of classified advertisements, newspaper articles, and even a couple of court cases in the 19th century. Following the publication of Fried’s work, Jensen further embarrassed himself in a couple of response comments in which he frantically defended his scholarship by misstating the evidence against it – all easily dispensed with by Fried as well.

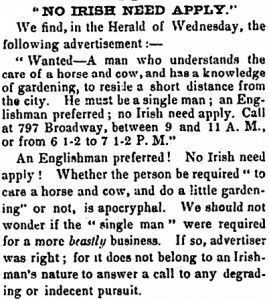

Intrigued, I decided to do a quick NINA search in a couple of online newspaper databases. The evidence is overwhelmingly in Fried’s favor, such as this 1851 note in an Irish news weekly from New York City:

In fact, a number of Irish community periodicals in the 1850s and 1860s seemed to relish in calling out discriminatory businesses that posted NINA ads.

Searching for NINA in genealogybank.com and newspapers.com – two subscription newspaper database websites – yielded 808 and 856 hits between the years 1800 and 1900, respectively, with the peak taking place between roughly 1850 and 1880. Most appear to be classified ads seeking labor. A few are Irish community commentaries upon the prevalence of such ads, further refuting Jensen’s additional claims about whether Irish immigrants were historically aware of such discrimination on a large scale.

The entire episode is a telling commentary on the weaknesses of the peer review process in academia, as quite frankly Professor Jensen’s piece probably should not have ever been published given its obvious deficiencies. Yet Ms. Fried’s also attests to the good that a little diligent scrutiny may bring upon bad historical claims.

ADDENDUM:

Upon seeing that Professor Jensen continues to aggressively defend his original thesis in comments at IrishCentral, a website covering this story, I decided to probe a little further. Jensen attributes much of the NINA slogan to an 1862 song by that title that became popular within the Irish community. Yet by limiting the search to 1861 and earlier, it immediately becomes apparent that the NINA practice was already well established. In a quick search I was able to locate some 200 hits for the term before the publication of the song.

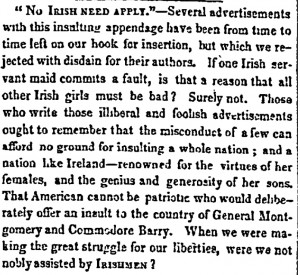

It also became apparent that the practice was also sufficiently established by as early as 1830 that the New York Morning Herald (July 12, 1830) ran the following announcement that the offensive NINA advertisements would be refused by their office:

It’s time to throw in the towel, Professor Jensen. There is no shame in changing a historical interpretation to reflect newly discovered evidence that has since come to light.