May 26, 1854 marks the 159th anniversary of the Burns Affair wherein a group of Boston abolitionists attempted to free Anthony Burns, a fugitive slave, from federal custody on the eve of his return to his owner. The plan to liberate Burns was initiated under the cover of a large anti-slavery rally at Faneuil Hall organized by Theodore Parker.

At the height of the rally a small band of abolitionists led by Thomas Wentworth Higginson – an abolitionist radical & future Grover Cleveland classical liberal – slipped away to the nearby courthouse in an attempt to spring Burns from the cell where he was being held. The cue to move was reportedly given by a young Edward Atkinson, the future famed free trade and anti-imperialist pamphleteer – who watched for a moment when the federal sentries had their guard down.

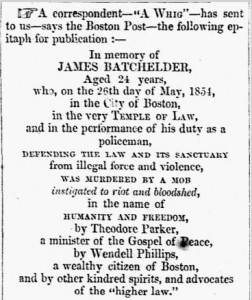

Higginson’s raiders pressed into the building but were repulsed by a cadre of federal marshals, a motley mixture of deputized brawlers from the local political machine and patronage appointees. One of the marshals fell in the ensuing chaos and died of still-unknown causes, among them an oft-mentioned possibility of friendly fire or even accidental stabbing by one of the other law enforcement officers present. The deceased, James Batchelder, was the first U.S. Marshal to fall in the course of regular duty, though he fell for the ignoble cause of a slave-hound.

The federal government’s response to the incident was ferocious and swift. A hearing the next day decreed Burns’ return to his Virginia owner and the full force of the federal government was unleashed to escort him southward. Over the course of the next week a veritable army of over 2,000 men arrived, mobilized upon, and militarized the streets of Boston. They consisted of the U.S. Marine Corps, an artillery unit from the army, coast guard personnel to facilitate the transfer by ship, and several hundred newly deputized federal marshals. In total, the cost of Burns’ extraction and return a week later was estimated to have exceeded $40,000 by 1850s standards.

While Burns lost his case, his cause and the overbearing federal response to it served as a rallying cry to the abolitionist movement. A group of philanthropists raised the money to buy Burns his freedom the following year, and the abolitionists arrested in the plot were able to escape conviction through a careful and largely successful legal strategy of procedural motions and the effective threat of jury nullification.

It also marked a turning point in abolition strategy, as its participants turned increasingly against politics as a means of combating the slave system. Henry David Thoreau recounted the incident in his journal, later converted into a powerful but little-known abolition speech:

“I walk toward one of our ponds; but what signifies the beauty of nature when men are base? We walk to lakes to see our serenity reflected in them; when we are not serene, we go not to them. Who can be serene in a country where both the rulers and the ruled are without principle? The remembrance of my country spoils my walk. My thoughts are murder to the State, and involuntarily go plotting against her.”