Earlier this month the Chronicle of Higher Education ran a feature about an ongoing debate between economists and historians over the relationship between slavery and capitalism. While some of the divergences between the two fields are methodological, they center upon the interpretation of evidence. The historians involved are all primary players in what has been called the “New History of Capitalism” (NHC) movement – a still vaguely defined post-“Great Recession” surge of scholarly interest in topics of economic history, and particularly slavery. A string of books in the early 2010s by Edward Baptist, Sven Beckert, Walter Johnson and others have advanced what they purport to be a “new” argument about the historical relationship between slavery and capitalism. These authors all advance sweeping theories of “capitalism” that situate slavery and slave-derived products such as cotton at the center of the global political economy between the early stirrings of the Industrial Revolution in 18th century Britain and the end of the American Civil War. In doing so, they all claim to break with an older branch of economic history that viewed slavery as antithetical to free-market capitalism on account of a number of efficiency arguments for free labor.

Much of the NHC literature is explicitly pejorative in its treatment of capitalism, thus the drive to link it to slavery and its many illiberal progeny in the century and a half since its abolition. Beckert specifically contends that slavery demonstrates “capitalism’s illiberal origins,” and portrays its history as one of expropriation and exploitation rather than growth and abundance. Baptist makes similar arguments while also attaching a pronounced sense of novelty to his own interpretation – a story of the exploitation and torture of slaves for economic gain that’s “never been told,” as his book’s title proclaims.

Given the intersection of my own research and the topic of slavery, I’m often asked what I think about the contributions of Beckert, Johnson, Baptist and other contributors to the NHC genre. The answer: not much.

I could echo what others have said about the NHC literature’s historical shortcomings, such as this piece by Alan Olmstead and Paul Rhode, or its misuse of basic economic concepts, as Bradley Hansen has shown in a widely cited blog post. Both are damning in their own right. I continue to be struck though by another feature of the main NHC works on capitalism and slavery, which returns me to the point about their exaggerated claims of originality. Consider the following passage, which (save for a few dated idiosyncrasies of language) could double as a brief summary of where Beckert, Baptist, and Johnson situate slavery in relation to global capitalism:”

“Slavery is not an isolated system, but is so mingled with the business of the world, that it derives facilities from the most innocent transactions. Capital and labor, in Europe and America, are largely employed in the manufacture of cotton. These goods, to a great extent, may be seen freighting every vessel, from Christian nations, that traverses the seas of the globe; and filling the warehouses and shelves of the merchants over two-thirds of the world. By the industry, skill, and enterprise employed in the manufacture of cotton, mankind are better clothed; their comfort better promoted; general industry more highly stimulated; commerce more widely extended; and civilization more rapidly advanced than in any preceding age.”

That passage was written in 1856. It comes from a widely circulated late antebellum tract by David Christy, a Cincinnati-based journalist and political economist who took up the task of “proving” that “King Cotton” was the engine of the world’s economy. This argument held that the integral position of cotton on a global stage made it indispensable to the financial and commercial wealth of the United States for the then-foreseeable future. The slave system, it followed, economically benefited even those persons in the north and in Europe who pushed the doctrines of emancipation and abolition from afar.

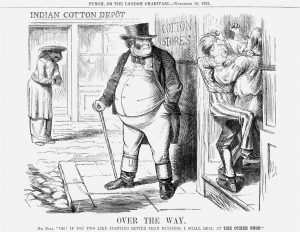

If this is starting to sound familiar, it is likely because the “King Cotton” thesis gained a champion from the radical pro-slavery politicians of the late antebellum United States – first as an argument against antislavery agitation, and then as a basis for the Confederacy’s blunderous foreign policy of attempting to draw the European powers – and particularly Britain – to their side in the Civil War with the lure of cotton. In the end the southerners miscalculated. They believed their own rhetoric about cotton’s claimed preeminence in the global economy and believed that both the carrot of its product and the stick of restricting supply would gain them diplomatic recognition and military aid from abroad. Instead, Britain simply turned elsewhere for the crop and resisted southern overtures to enter the war, particularly after the Lincoln administration took an increasingly bolder stance against slavery.

The failure of King Cotton to stave off abolitionist agitation and, later, secure the Confederacy’s place diplomatically is its own evidence that the underlying thesis severely exaggerated its own importance to the global economy – even at the high water mark of the American plantation system on the eve of the Civil War. This chain of events raises an interesting historiographical twist for Beckert, Baptist, and Johnson though. Far from the novel and necessary course correction to economic history that its contributors claim to be offering, the burgeoning NHC literature on “slavery and capitalism” has almost unwittingly stumbled into a project of rehabilitating the antebellum King Cotton arguments of David Christy, Louis Wigfall, and James Henry Hammond.