Allen Guelzo of Gettysburg College is presently engaged in a willfully mendacious portrayal of my ongoing research into Abraham Lincoln’s Civil War era colonization programs. This is not a lightly proffered criticism, but it is one I make note of to differentiate it from the honest interpretive disagreements that historians often have when considering a controversial subject, and to call attention to a breach of professional ethics in Guelzo’s characterizations of my work.

The article by Guelzo that prompted this post recently became available without a paywall and may now be found online here. A response that I co-authored with my colleague Seb Page shortly after the original piece appeared in print is available for download here. I invite my readers to evaluate both pieces, and to subject our work to all due scrutiny.

Both articles are lengthy and address the particulars of our extended dispute in depth.

For this blog post though I’d like to take up the issue of the most serious charge, as it is where Guelzo’s crossing of the line between interpretive disagreement and professional misconduct becomes pronounced. Guelzo charges me with an act of intentional historical contrivance, or as he puts it “cit[ing] documents that do not exist and then smother[ing] their non-existence with invocations of “mystery”” and of artificially attaching Lincoln’s name to records generated by others around him.

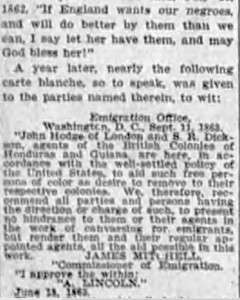

The specific document in question is a June 13, 1863 authorization for two colonization schemes to be carried out in partnership with the British Government in their Caribbean holdings of British Honduras (modern day Belize) and Guyana. It is historically significant as an attestation of Lincoln’s continued colonization enterprise that postdates his final Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, where many historians have posited that he abandoned the idea of voluntary black resettlement (it is also far from the only document of this type). It is also certain that Lincoln signed the document, as this is attested in both an eyewitness account of the meeting that produced it and by multiple surviving copies that clearly show the presidential endorsement.

Guelzo disputes this fact though, and uses his contention as the basis of both his counterargument on colonization and his personal insinuation of scholarly impropriety in my handling of the document. In a meandering flourish of misconstruction around the evidence that was provided in Colonization after Emancipation and elsewhere, Guelzo asserts that this document “is not a Lincoln document,” accuses us of “supply[ing]” Lincoln’s signature in a place where it was not affixed, and strongly insinuates intentional malfeasance on our part, specifically through “the liberty of manufacture” of a historical document to bolster the case of Lincoln’s post-emancipation colonization efforts.

Much of Guelzo’s case against this document’s authenticity intentionally exploits the fact that the original (or actually two originals that Lincoln handed to the agents of each colony on that day in June 1863) did not survive the passage of time, having last been seen in the early 20th century. This is not an uncommon problem with historical documents, and even famous ones. The original Emancipation Proclamation was lost in the Chicago Fire of 1871. What Guelzo does not acknowledge though is that Lincoln’s June 13, 1863 order – complete and with his personal endorsement intact – was enrolled in multiple public records at the time of its creation. It was then replicated and widely disseminated with instructions to British colonial administrators so that they might begin to receive the American ex-slave colonists.

In the interest of the full and open scrutiny I have invited, it is of use to illustrate the document’s verifiable provenance and make it available for review.

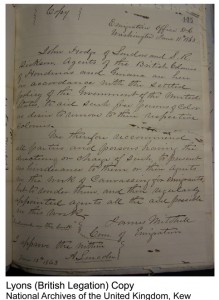

On the day of its issuance a copy of the document – including Lincoln’s endorsement – was delivered and logged at the British Legation in Washington, D.C. It was eventually transferred to the National Archives of the United Kingdom, where it still resides today. A photo of this document was also made available to Guelzo on page 72 of Colonization after Emancipation, though he chose to ignore it.

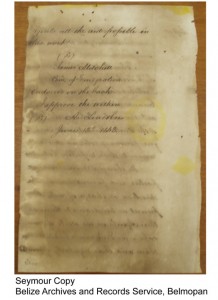

A second copy was made at the time for Lt. Governor Frederick Seymour of British Honduras. It was carried to him by one of the land agents, John Hodge, on the next ship to Belize City in August 1863. It currently resides in the Belize Archives and Records building in Belmopan.

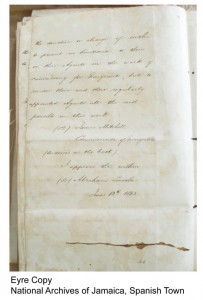

A third copy was sent to Lt. Governor Edward Eyre of Jamaica. Eyre had been given supervisory jurisdiction over all black colonization schemes in the British Caribbean by the British Colonial Office. It currently resides in the National Archives of Jamaica.

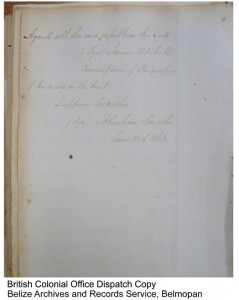

A fourth copy was transmitted back to the British Colonial Office in London, and formally disseminated in a packet of instructions to the affected colonial governments in September 1863. One of these is also held in the government archives of Belize.

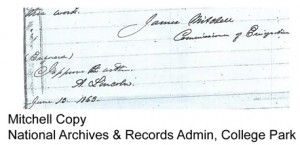

Mitchell also retained a copy in the surviving portion of the U.S. colonization office records. It is held by the National Archives and Records Administration.

And a lost original, of course, was viewed by a reporter for the Macon Telegraph in the early 20th century shortly before its disappearance. He reprinted the document in full, as I’ve discussed previously on this blog.

Of course all of this raises an important question: if not Lincoln’s own pen, exactly where did this document come from? And why was it formally enrolled and circulated across the British Empire back in 1863, some century and a half prior to the alleged “liberty of manufacture” that brought it to public light?

Your move, Allen.