The history behind the founding of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) almost always begins with the case of Edward A. Ross. A prominent economist and sociologist in his day, Ross was forced to resign from his faculty position at Stanford University in November 1900 after running afoul of the political views of the university’s surviving namesake, Jane Stanford. Ross’s dismissal set into motion the events that culminated in the founding of the AAUP, some fifteen years later.

The incident prompted John Dewey to compose a formal defense of academic freedom in the January 1902 issue of Educational Review, which later served as the basis for the AAUP’s own founding principles. The American Economic Association also conducted an investigation into the episode under the charge of Columbia University’s Edwin R.A. Seligman, severely chastising Stanford’s actions. Ross’s dismissal even precipitated a wave of faculty resignations from Stanford in protest, starting with his philosophy department colleague Arthur Lovejoy. Dewey, Seligman, and Lovejoy would all go on to become the principal charter members of the AAUP, as well as early presidents of the organization. Lovejoy would later identify the Ross case as a crucial precipitating event in the formation of the organization. Seligman took charge of organizing what became the organization’s main investigative body, the Committee A on Academic Freedom. And Ross himself would later go on to hold several positions within the leadership ranks of the AAUP.

While political events certainly precipitated Ross’s forced resignation, a fair amount of confusion and mythology have come to characterize the exact nature of his disagreement with Mrs. Stanford. Ross and Stanford had previously clashed over the former’s support for William Jennings Bryan and the free silver movement during the 1896 election. He also allegedly criticized Jane Stanford’s late husband, California railroad baron and politician Leland Stanford, and further irritated her by advocating for municipal ownership of street railroads and utilities. The most immediate source of their tension though was a speech that Ross gave a few months prior to his dismissal in which the professor argued for the strengthening of immigration restrictions on Chinese and other Asian laborers.

While acknowledging that Ross’s position on Chinese labor displayed a number of ugly racial undertones, the cause of the dispute itself is normally presented as a political struggle between Ross’s own strident progressivism and the politically conservative, moneyed interests of Mrs. Stanford and the railroad industry. The Stanford fortune, after all, came from a company that widely utilized Chinese laborers to construct its railroad lines. One version of the episode on the AAUP website even portrays Ross’s comments as “statements about railroad monopolies” – a substantially more innocuous cause than barring immigrants from entering the country. Another AAUP account states that Ross was dismissed for speaking out “against privately owned railroads and Chinese immigration” and heavily implies that the latter issue was only a derivative of the former, on account of the railroad tycoons habits of using Asian labor.

The framing of the case as a battle between labor and the capitalist classes owes much to Ross’s own publicity campaign after his resignation, including a vocal self-portrayal as a martyr to free speech and to the values of the progressive political left. Ross organized an effective PR campaign by taking his case to the newspapers and enlisting other prominent academics from around the country to speak out on his behalf. In doing so he painted himself as a defender of the white working class against railroad industrialists and robber barons.

Somewhere along the way, the retelling of this storied episode became separated from the immediate events that precipitated it. The earlier dispute over Bryan, the fight against railroad monopolies, and Ross’s progressive criticisms of the Stanford family fortune rose in prominence as secondary or even co-equal causes for his forced resignation. Ross’s remarks on Chinese immigration, while still acknowledged as a cause and condemned for taking a position that we now recognize today as racist, have lost their original specificity. His original remarks do not appear to have been reprinted in full since the San Francisco newspapers covered the story shortly after Ross’s resignation.

This missing context is crucial, as they show that Ross went well beyond simply advancing a general economic argument against Chinese immigration, or expressing concern for worker conditions against the anti-labor antics of the railroad industry. Rather, his comments included an elaborate endorsement of racial eugenics and concluded on a bombastic appeal to Aryan nationalism.

While we should recognize that Ross’s comments reflected a racial sentiment that was more common in his time than our own, Mrs. Stanford’s objections to them were also directly rooted in an objection to their prejudices and a belief that Ross intended them to inflame racial animosity against persons of Asian descent. They were also the unambiguous and immediate instigator of Ross’s dismissal. Other disputes such as the Bryan campaign and general labor agitation only reflect an ongoing history of tensions between Ross and Mrs. Stanford.

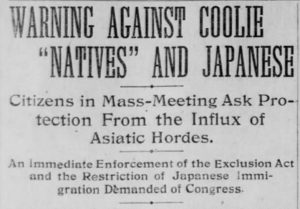

The precipitating event happened on May 7, 1900 when Ross addressed a large public assembly on the “problem” of Chinese immigration. The meeting was overtly racist in character, featuring a succession of speakers who railed against the “Asiatic hordes” of immigrants. They adopted a resolution calling on Congress to expand the Chinese Exclusion Act, and extend its provisions to the Japanese, who allegedly mimicked American customs which “makes them more dangerous as competitors.” The San Francisco Call published a summary of Ross’s speech on May 8, 1900, as follows:

“[Ross] declared that primarily the Chinese and Japanese are impossible among us because they cannot assimilate with us; they represent a different and an inferior civilization to our own and mean by their presence the degradation of American labor and American life. We demand a protection for the American workmen as well as for American products, the speaker insisted. And should the worst come to the worst it would be better for us if we were to turn our guns upon every vessel bringing Japanese to our shores rather than to permit them to land.”

Jane Stanford read this summary in the newspaper and became incensed. As documented by historian James C. Mohr, she penned a letter to Stanford University president David Starr Jordan the next day stating that Professor Ross “should now be dismissed.” Mrs. Stanford made it absolutely clear that her grievance with Ross, though preceded by other disputes, derived in this case from his race prejudice. Using his university title, Ross had ventured “out of his sphere, to associate himself with political demagogues of this city, exciting their evil passions, drawing distinctions between man and man, all laborers and equal in the sight God, and literally plays into the hands of the lowest and vilest elements of socialism.” She also expressed concern that Ross’s inflammatory rhetoric could lead to violence, and compared them to an anti-Chinese racial riot in San Francisco some two decades prior that resulted in the racial murders of four Chinese immigrants and left much of the city’s Chinatown section in flames. It too had started as a “labor rally” to call for greater immigration restrictions. As sole trustee of the university, she instructed Jordan to provide Ross with “notice that he will not be re-engaged for the new year.” (Stanford to Jordan, May 9, 1900, Stanford University archives)

Ross, Jordan, and Stanford engaged in a protracted negotiation over the course of the summer, with Jordan attempting in various degrees to prod Mrs. Stanford to back down from her demand. By early autumn however they had reached an impasse, and Ross prepared for his resignation – as well as an accompanying publicity campaign to draw attention to his cause. He wrote his mother on September 9 about both the state of affairs surrounding his job and the cause of the dispute, saying nothing of Bryan, of free silver, or of his calls for publicly owned transit and utilities. He stated one cause alone, and that was the Asian immigration speech:

“Last May at Dr. Jordan’s suggestion I spoke at a mass-meeting to protest against Japanese and Chinese coolie immigration. I argued against letting in the coolies and the big Railroad people who want cheap yellow labor induced Mrs. Stanford, who is now very old and crochety, to dismiss me.”

Ross noted that he was timing the announcement so as to “make a sensation on the Pacific slope” with the press. Other correspondence uncovered by Mohr suggests that Ross intentionally coordinated his public departure for November so as to generate publicity for the release of his forthcoming book, Social Control.

It is the elusive text of Ross’s speech at the May 7, 1900 rally though that demonstrates the full severity of his racist and eugenic objectives. Several San Francisco newspapers as well as William Jennings Bryan’s newsletter obtained copies of it from Ross in November around the time of his public resignation. A key excerpt of the text appears below, as reported in the San Francisco Chronicle on November 15:

Ross’s eugenic and racial objectives are a pervasive theme of his remarks, including a dire warning of a coming white “race suicide” in the face of declining birth rates compared to Asian populations. Notably, Ross is the academic who first popularized the overtly white supremacist theory of “race suicide” in a 1901 address to the American Academy of Political Science. That address was one of the many fruits of his highly effective publicity campaign to extol his own martyrdom the previous year. Therefore one of Ross’s most notorious scholarly contributions actually takes its root in the political speech that led to his dismissal from Stanford. Ross concluded his remarks with an equally inflammatory pledge to preserve California for the white race: “California, this latest and loveliest seat of the Aryan race, shall not become, if we can help it, the theater of such a stern wolfish struggle for existence as prevails throughout the Orient.”

The severity of these remarks alone is cause to revisit Jane Stanford’s stated concerns with Professor Ross’s activities. While her objection was political in nature, the character of Ross’s statements involved a grossly inflammatory racial appeal – even by the standards of the day. Her concern that this appeal could instigate racial violence was not unfounded.

That much acknowledged, cases such as the Ross episode are noteworthy precisely because they test the limits of academic freedom. While irresponsible, demagogic, and undeniably made in appeal to the basest racial prejudices of his day, the question of whether Ross’s comments warranted the protections of free speech also directly led to the formalization of academic freedom by Dewey, Seligman, Lovejoy and others under the auspices of a new organization, the AAUP.

It is important to remember this early precedent, as the cause célèbre that birthed the AAUP involved an incident of extremely offensive speech in support of a cause that we may rightly condemn as not only racist but maliciously so. To put it bluntly, Ross advanced an argument for racial eugenics amidst a call to arms on behalf of Aryan nationalism at a populist labor rally in a city with a very recent history of racial violence. The founding members of the AAUP believed that argument was nonetheless a protected exercise of academic freedom, and subsequently built their organization upon its direct fallout. What that entails for the modern AAUP is necessarily a matter of retrospection, albeit one that should be engaged on account of the organization’s own modern relationship to the ongoing academic freedom debate.