The fun continues with the adjunct activist crowd in the wake of my Journal of Business Ethics article with Jason Brennan (who has an interesting challenge up for all the “social justice” claimants on the other side of the issue). Unfortunately, most of the comments we’ve received continue to display little evidence of actually reading our paper. And most of the exceptional examples that do largely fail to engage the main argument we make about the existence of tradeoffs in pursuing “adjunct justice.” Nonetheless a few additional points are worth commenting upon. Continuing in the same vein as my post from the other day…

“But the adjuncts are being exploited!”

That’s certainly an interesting normative claim. It does not however challenge or alter what was, at its core, a positive argument to demonstrate the existence of tradeoffs in attempting to deliver higher pay to adjuncts as a class. Those tradeoffs are a product of scarce resources and university budget constraints combined with the fact that demand curves do indeed slope downward, including in labor markets. They exist independently of whether or not exploitation is occurring in the adjunct market. I might fully accept your assertion that adjuncts are exploited, and the very same tradeoffs we’ve presented would still exist and still constrain your efforts to deliver upon adjunct justice.

Alternatively, I might challenge elements of your exploitation framework. I might argue, for example, that adjuncts tend to be highly educated people who have an abundance of exit options to comfortable and well-paying jobs outside of academia. While this may not necessarily obviate all exploitative characteristics you ascribe to adjuncting, it probably reduces the resonance of their “plight” and the urgency of prioritizing their claimed exploitation over other problems. Or I might answer that what you describe as “exploitation” is actually a misdiagnosis of a situation in which some adjuncts are making highly unreasonable salary demands relative to the work they perform and the qualifications of they possess. A 4-4 teaching load covering about 30 weeks of the year with minimal or no research and departmental obligations is a far cry from a full-time job, especially compared to the 50 work week 9am-to-5pm norm. It also entails significantly fewer work obligations than the typical junior level full time faculty position. So perhaps a better place to start the exploitation discussion is by explaining your use of the term. Perhaps you will convince me, as I am not wedded to the foregoing challenges – I only raise them since they do not seem to have been considered when you attributed exploitation to the adjunct situation as if it were a broadly-encompassing and established matter of fact.

But even then, it’s not clear what you’re adding. Although you take “exploitation” as a given, the issues I note here suggest a need to further explore whether and to what degree adjuncts are being exploited before we may even proceed to the implications of your normative addendum. And when we do proceed to those implications, they still do not meaningfully alter the reality that any effort to alleviate them will be constrained by the same sometimes-unpleasant tradeoffs that we originally presented.

“It would take something much higher than the basic living wage that adjuncts desire to induce the job gentrification effects you describe.”

First off, you need to define a living wage if you intend to use the term. I make this request in all seriousness, noting that while your tone suggests it may be a relatively modest pay hike, other adjunct activists have endorsed the SEIU’s $15K per course solution in complete seriousness. That solution would yield an adjunct $120,000 a year on a 4-4 load with summers off. At that rate, I’d even quit my job and assist to gentrify the full time adjunct market. So I assume that when you use the term “living wage” you have something else in mind than the SEIU proposal.

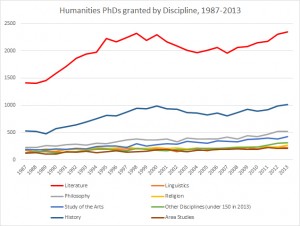

So let’s go a more modest route and assume you mean $6,000 a class as the new adjuncting norm. At the same 4-4 course load, that translates into $48,000 a year. We don’t even need to hypothesize a job gentrification effect at that level because we may also witness its reality every day in the present academic job market. $48,000 also happens to be well within the range of the median starting salary for an entry level full time faculty position. In several of the humanities where the adjunct problem is strongest, positions at this level are besieged by dozens or even hundreds of applicants. English in particular suffers from a massive overproduction of PhDs and a large cohort of residual job seekers from previous years. These conditions are prime for the job gentrification effect we describe.

Still not convinced? Well, you could offer $4,000 a class, or a salary of $32,000 a year on a 4-4 load. While it may not be as pronounced as the national median of $48,000, I’ll gladly wager that you will still have a gentrification effect. Yes, the academic job market in some fields is actually that saturated. In fact it’s so saturated that many adjuncts routinely complain that they are underemployed, i.e. they cannot find enough classes even at the current national average adjuncting rate of $2,700 per class. Any increase in adjunct pay will therefore tap further into that already-saturated market and, eventually, entice others to enter it. If those entrants tend to have PhDs in hand, their credentials will already exceed the majority of current adjuncts, who do not possess terminal degrees as a rule. And that is where the gentrification occurs.

“You’re just anti-union, and you don’t want adjuncts to be able to organize.”

While this is not a serious counterargument to our paper, it is true that I would not personally join an adjunct union. I would not join one because I see no benefits that I could derive from joining one, and I see many downsides including the union’s short-sighted pursuit of policy objectives that I believe would actually harm most current adjuncts. You may believe differently for your own situation, in which case you should be free to join a union.

What I struggle to understand though is your assumption that unions are innately good for all adjuncts. I can think of a number of reasons why this is not the case. Specifically the adjunct unions are advancing many of the very same proposals that are vulnerable to the tradeoffs scenarios we describe in our article – the same tradeoffs you are curiously reluctant to engage. These include measures that would likely impose considerable strain upon university budgets, induce job gentrification effects in the saturated quarters of the humanities market, and prompt universities to create a smaller number of full time positions by laying off the majority of the adjunct workforce and consolidating its classes. In fact, we’ve already started to see evidence of what happens when universities begin converting large numbers of adjunct positions to a smaller number of full time positions: the adjuncts do in fact lose their jobs.

I would also decline membership in an adjunct union because I believe that its goals are not representative of a sizable minority of the adjunct workforce – the working professionals who also moonlight in the classroom for 1-2 courses a semester. This not only pertains to my own teaching obligations, but roughly a quarter of all current adjuncts in the United States. Many adjunct unions are currently pressing for one-size-fits-all compensation arrangements as well as seniority privileges in adjunct hiring decisions. Both of these proposals are likely to harm the many working professionals who adjunct – the first because it may actually impede the pay level differentiation that is necessary to attract professionals to the classroom, and the latter because it would privilege long term “career” adjuncts with weaker credentials over better-qualified (and younger) professionals in competitive hiring decisions.

I do not oppose the right of persons to form a union, provided that they do not require unwilling adjuncts to join the union they form. Unfortunately, many adjunct union initiatives are seeking a closed shop arrangement where all adjunct faculty are required to join (at least in states that permit such things). We’ve also seen real world examples of the SEIU behaving badly in attempting to bring these arrangements into existence. Just last month a popular professional adjunct at Georgetown University was forced out of his job by the SEIU’s closed shop arrangement. This followed months of harassment of the adjunct, including SEIU reps stalking him to the university parking lot after his classes and verbally disparaging him for his now-founded opposition to joining their union.

“Everything you state about the tradeoffs of university budgeting is already obvious.”

Good, because I fully believe that the tradeoffs are obvious. I’m not convinced that most adjunct activists recognize them as obvious though, because a number of them are presently bombarding me with angry and inflammatory rants in which they insist that the tradeoffs we’ve identified do not exist. Or in which they offer ridiculous and unrealistic non-solutions that we already addressed in portions of the article that they did not bother to read.

I am also somewhat unconvinced that even you recognize the tradeoffs as obvious, despite your claim to do so. While you do indeed identify them as “obvious” and purport to recognize the constraints they impose, you too fail to meaningfully engage their implications. When I caution you about the job gentrification effect, you deny its existence or assert against all evidence that it somehow doesn’t apply to adjuncts. When I note that there seem to be no immediate pots of gold in the university budget to meet the level of “adjunct justice” you desire, you insist otherwise but do not bother to explain where it may be found. When I suggest that there may be multiple other more-just claimants to university resources than adjuncts, you insist that I’m trying to impose some sort of false dichotomy upon you and then proceed to act as if we might provide justice to all simultaneously without concern for the price tag. And when I point out that your favorite pot-of-gold funding source, university administrative bloat, includes a litany of student activist offices, green sustainability initiatives, campus diversity centers and other ideological causes that you personally support, you suddenly become non-committal about defunding those areas of “badmin.” Or you offer ad hoc reasons to justify their existence. In short, while you pay lip service to recognizing the tradeoffs I describe, you also display a habit of revealing preferences that suggest either you don’t actually understand them or you are unwilling to seriously engage their implications.

“You’re wrong about the tradeoffs favoring stakeholder group X. Here’s a reason why adjuncts have a stronger social justice claim than they do.”

Actually we intentionally took no position on who has the more just claim. Though you undoubtedly found this unsatisfying, remaining neutral on that question was necessary. It allowed us advance the discussion on a topic where a majority of the participants are still adamantly hostile to the notion that any tradeoffs exist at all. Taking a position on the preferable tradeoff solution at that time would have been a distraction to that necessary first step. In fact, your eagerness to assign us a position anyway when we did not take one is its own evidence of precisely the type of distraction we were aiming to avoid, at least until the existence of tradeoffs was more widely acknowledged in the adjunct debate.

But since you’re eager to go down the route of specific solutions, let’s hear you make your case! Tell me why you think the adjuncts have a more socially just case to benefit from university resources than, say, students. Or taxpayers. Or the student activities office that wants to build a lazy river next to the rec center. I’m sure there are arguments to be made for each, and I’m somewhat intrigued as to whether yours will be convincing. Even as I do hold my own rank ordered preferences that are likely different than yours (especially given that you’ve placed adjunct justice on the very top), I never claimed that the matter was settled or that I know the “right” answer to a very complex problem.

But in order to give it the full consideration it deserves, you will also need to move beyond haranguing me over a position I did not take and actually make the case for the position that you believe to be your strongest case.

“The madjuncts are justified in being upset with you and acting out in rage.”

I don’t really care if they’re justified or if you think they’re justified, as it really doesn’t bother me one way or another that they’re upset with me. Challenging ideas can be upsetting, and I do not subscribe to the ideology of “safe spaces.” I do however consider the way they frame their responses to be a useful signal in deciding whether I should treat their arguments as a credible component of this discussion. Right now and based on the evidence (which I nonetheless find hilarious), I lean against.

“Your motives for writing this article are hateful/concealed/ulterior/evil, and you’re inexplicably angry at adjuncts.”

I cannot stop you from assuming whatever you like about my motives. You still haven’t addressed my arguments, and attacking someone’s assumed motives in lieu of his/her arguments is a grade school fallacy.

That said, my actual motives for writing this piece are pretty straightforward. I work in a university environment and study trends in higher education. I also have first-hand familiarity with adjuncting. And in following the public discussion of the “adjunct crisis” over the past several years, I noticed it was plagued by erroneous data claims, non-existent economic analysis, a preference for frivolous “activism” over scholarship, and a general lack of peer reviewed literature. So I started to work on several projects to elevate the discussion of a topic that had been neglected on a scholarly level into suitable peer reviewed outlets.

I’ll also plead guilty to one ulterior motive: it added some nice lines to my CV.

In the process of researching this topic I did encounter a number of deeply unprofessional and unscholarly agitators and malcontents that might be collectively dubbed “madjuncts” (and note that most adjuncts are not madjuncts – just the small but loud cadre of activist types who offered many of the inane “rebuttals” I addressed in my previous post and, to some degree, here). And believe it or not, I actually ignore most the madjuncts. I engaged a few of them directly, only to discover that they were not serious contributors to the discussion. In assuming all manner of evil motives on my part, many of these people have also projected their own anger onto me. Yet truth be told, I still find them amusing for their ridiculousness and, at most, only mildly annoying for their habits of eschewing scholarship in favor of a broken record of activist talking points. Though I do occasionally indulge in humor at their expense, I also find that a few of them are impossible to parody…which is also amusing. Real life can be stranger than an Evelyn Waugh novel or a Mel Brooks movie. Living, breathing Ignatius J. Reilly types, albeit with a Slavoj Zizek twist, seem to gravitate to that small but loud madjunct basement of the adjunct world. Some of them have taken to sending me very strange pieces of hate mail, only further validating my initial assessments of the “activist” crowd. And a few, from time to time, explode in profanity-laced online tirades…which are also amusing to read.

But the one thing they don’t do is glaringly obvious: the madjuncts don’t actually do research. They don’t produce meaningful scholarly work and they don’t publish anything of substance in academic venues. Melissa Click has a more robust CV than the activist madjunct archetype, and she writes utterly silly articles about Foucauldian power dialectics in the Twilight series. Or something. The madjunct activists don’t even reach that low level of pseudo-scholarship, be it in their own respective fields or in their claimed knowledge of the adjunct problem. And though they profess to be full time “activists” for a largely counterproductive strain of the adjunct cause, that complete absence of scholarship effectively makes them non-players in the intellectual dialogue about U.S. higher education.