In a previous post I criticized a number of Alexander Hamilton’s modern biographers for attempting to reinvent him as an “abolitionist,” or at least a staunch and principled antislavery man. The evidence for this claim is exceedingly weak, although Hamilton, who handled numerous financial transactions involving the sale and purchase of slaves for his wife’s extended family, might be more accurately characterized as a moderate antislavery man who was nonetheless a direct beneficiary of the institution on numerous occasions and certainly did not prioritize the cause of its elimination amidst his political objectives.

Yet the portrayal of Hamilton as an abolitionist is pervasive, including a number of “conventional” stories that have no basis in historical evidence. Let’s consider a few more:

Slavery in Hamilton’s Childhood

One common feature of Hamilton biography concerns the purported role of slavery in his upbringing. Hamilton was born on the Caribbean island of Nevis and spent much of his childhood on St. Croix, witnessing the institution first hand. On this basis, his most prominent recent biographer Ron Chernow asserts that “The memories of his West Indian childhood left Hamilton with a settled antipathy to slavery.” Similar claims appear in most other works from the Hamilton literature that reference slavery.

Curiously, this claim is made without any primary source attestation. Surviving records indicate that Hamilton’s mother owned two slaves including a boy named Ajax who was assigned to serve her son (he was denied inheritance of this slave on account of his illegitimate birth). Yet none of Hamilton’s writings claim antislavery sentiments from this or any other episode of his childhood – it is simply assumed by biographers who have already accepted the inflated claims of Hamilton’s “abolitionism” from later in life and projected them backwards onto his childhood. “This early exposure to the humanity of the slaves may have made a lasting impression on Hamilton,” notes Chernow – except that there’s no evidence whatsoever that it did. The entire claim is little more than a fairy tale.

Slavery and Hamilton’s Political Career

As I documented in my last post, Hamilton’s antislavery reputation derives almost entirely from two events, neither of which provides compelling evidence for abolitionism or really anything more than a passing and moderate antislavery sentiment. First, Hamilton supported a proposal by John Laurens to offer freedom to slaves in exchange for their service in the Revolutionary War. While this was certainly a commendable overture for its time, it falls far short of establishing Hamilton as an “abolitionist” as opposed to recognizing an opportunity for military advantage (In fact, even Robert E. Lee endorsed a similar proposition in the closing days of the Civil War some three quarters of a century later – few credible historians would assign the abolitionist moniker to him on that account).

Second, Hamilton – like most of the New York political class – joined the New York Manumission Society in 1785. This was a moderate, gradualist antislavery group that favored compensated manumission drawn out across many decades. It also had multiple slaveowners among its ranks, and others – including Hamilton – who directly benefited from the institution through the patronage of his numerous slaveholding in-laws.

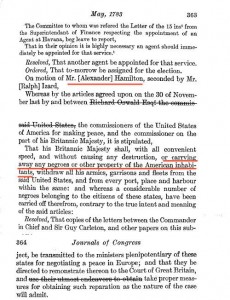

When it came to direct political action on slavery though, Hamilton was at best ambivalent. One illustrative example occurred in 1783 as the British government withdrew its remaining troops from the United States following the conclusion of the Revolutionary War. According to the terms of the preliminary peace treaty, Britain agreed to the restitution of certain properties – including slaves – during the revolution. Yet Britain had also adopted its own policy of offering freedom to slaves who escaped to their lines and fought for the loyalist cause during the war. At the time of the British withdrawal from New York City, their commander Sir Guy Carleton held around 3,000 of these loyalist freedmen. He eventually transferred them to Nova Scotia in order to fulfill this obligation and, possibly, prevent their re-enslavement. Carleton’s anticipated removal of the slaves predictably incensed a number of New York’s slave-owning families who wanted to reclaim their property, or at least receive payment for them. Hamilton was serving in the Continental Congress at that time and answered the call by introducing a resolution calling attention to this claimed breach of Britain’s obligations and directing American diplomats to press for the slaves’ return or restitution in advance of Carleton’s departure. It appears in the following excerpt from the journal entry for May 26, 1783:

The outstanding claim on the slaves that escaped to freedom under Carleton’s protection remained a point of diplomatic tension for the next decade, and Hamilton later pushed the Washington administration to seek only payment in exchange for the freedmen on the grounds that seeking their return would be fundamentally unjust after so many years. Yet Hamilton’s actions in 1783 also plainly illustrate that the well-being of the slaves themselves was a distant secondary concern behind the financial stakes of their former owners.

This pattern of subordinating the issue of slavery to other political and economic concerns whenever it arose was highly characteristic of Hamilton’s political career whenever he faced the issue. He was far from the worst man of the founding era when it came to the issue of slavery, but an “abolitionist” he was not – nor did he come anywhere close.