Dr Sir

Mrs. Renselaaer has requested me to write to you concerning a negro, Ben, formerly belonging to Mrs. Carter who was sold for a term of years to Major Jackson. Mrs. Church has written to her sister that she is very desirous of having him back again; and you are requested if Major Jackson will part with him to purchase his remaining time for Mrs. Church and to send him on to me.

…

I am with great regard Dr Sir Your obed servant

Alexr. Hamilton

New YorkNovr. 11. 1784

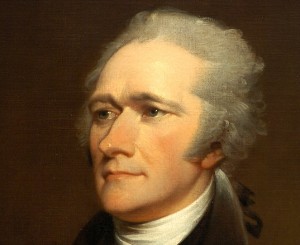

The U.S. Treasury Department’s recent announcement that they will soon be replacing Alexander Hamilton on the $10 bill has sparked a small movement to salvage the first Secretary of the Treasury’s place on the national currency. One recurring theme of the “save Hamilton” movement is to stress his antislavery credentials, with several commentators going so far as to rank him among the foremost “abolitionists” of the founding generation. He was a “staunch abolitionist” according to the New York Daily News, while this Huffington Post piece celebrates his “strong” opposition to slavery as a primary reason to keep him on the $10 bill. This designation extends far beyond amateur political commentary as a multitude of adoring Hamilton biographers attach the abolitionist and staunch antislavery labels to their subject matter.

“Few, if any, other founding fathers opposed slavery more consistently or toiled harder to eradicate it than Hamilton,” writes Ron Chernow in his much-praised assessment of the Federalist Papers co-author. Similar claims of his antislavery devotion appear in biographies by Richard Brookhiser, and even Forrest McDonald, a historian normally known for his empiricists’ rigor and close reading of evidence. There’s a major problem with this narrative though: the evidence of Hamilton’s “abolitionism” is vastly overstated, if it even exists at all.

Hamilton and Slavery

As the letter excerpted above reveals, Hamilton’s relationship with slavery is far from unblemished. It contains a bit of family business involving two of Hamilton’s sister-in-laws, Margarita Schuyler Van Rensselaer and Angelica Schuyler Church, and their desire to reacquire a slave named Ben who was, at the time, under lease to another political acquaintance. It is one of many such examples in Hamilton’s papers in which he acted as a financial agent for the sale, lease, or acquisition of slaves for his immediate family.

The details of these transactions were often sparsely recorded, yet several troubling entries appear. A 1784 cash book annotation for a client reads “To a negro wench Peggy sold him.” Another of his account books records “Cash to N. Low 2 Negro servants purchased by him for me, $250” dated 1796, and possibly corresponding to another slave transaction on behalf of his in-laws in the Church family. In a passage that Hamilton’s modern biographers usually tread lightly around, Hamilton’s own grandson described this entry thusly: “It has been stated that Hamilton never owned a negro slave, but this is untrue. We find that in his books there are entries showing that he purchased them for himself and for others.” Another entry from 1797 involving the same in-laws reads “John B. Church Dr. to Cash paid for negro woman & child 225,” and a related entry reads “ditto paid price of Negro Woman 90.”

Most of these transactions involved Hamilton’s relatives by marriage – specifically he wed the daughter of New York’s wealthy and politically powerful Schuyler family, which owned several slaves and used them as house servants. While such actions are not atypical for wealthy persons in the late 18th century, they show a recurring pattern in which Hamilton directly used slaves, conducted slave transactions for his family, and generally benefited from slavery from roughly the date of his marriage in 1780 until the end of his life in 1804 (New York abolished slavery in 1799 with a law that gradually phased the institution out by converting it to fixed indentures).

This is not to say that a slave-owner or beneficiary of the institution was incapable of harboring general antislavery sentiments, and Hamilton likely did. In 1785 Hamilton joined the New York Manumission Society, along with a large swath of New York’s political elite including John Jay, Melancton Smith, and Aaron Burr, among others. Though anti-slavery, the Manumission Society was at best a moderate and gradualist organization that focused most of its political efforts on ending the slave trade and slowly mitigating the institution by managed manumission and with indenture periods, as opposed to abolishing slavery outright. During his military career, Hamilton also supported a plan by Revolutionary War hero John Laurens to enlist slaves as soldiers for the American cause in exchange for their freedom. But these actions – upon which practically the entirely of Hamilton’s “abolitionist” reputation rests – are hardly the stuff of abolitionist activism, even by 1780s standards.

Keep in mind that Hamilton was a prolific newspaper editorialist, penning hundreds of typically pseudonymous tracts on all manner of political issues of his day. A striking feature of the Hamiltonian corpus is the general absence of any clear, unequivocal exposition of the “abolitionist” viewpoint so many of his biographers have attributed to him. In this respect, he stands in marked contrast to other prominent antislavery men of his era who wrote extensively on the subject. Consider John Adams, who despite compromising on the issue to retain the southern states in the nascent republic, made his moral objections to slavery clearly known. Or compare Hamilton’s silence to Benjamin Franklin, a slave-owner in his younger days who converted to the abolitionist cause and became an outspoken antislavery man by the end of his life. One might even look to Thomas Jefferson, owner of a large Virginia plantation who nonetheless wrote multiple works conceding the immorality of the institution and expressing his fears of what its future entailed for the United States. Hamilton, by contrast, seldom even referred to slavery in his writings beyond an abstract generalization and never approached the specificity of many of his contemporaries in engaging the subject.

All of this evidence does not discount the likelihood that Hamilton conceptually opposed slavery, as his manumission society activities reveal. But it does illustrate something that his primary modern biographers have been reluctant to concede: Hamilton routinely subordinated his antislavery inclinations to other family and political concerns, and he did not ever approach even a modest level of engagement on the issue in his otherwise voluminous published works. To place him nominally in the column of a slave-beneficiary who had qualms with the institution is probably accurate, but to call Alexander Hamilton an abolitionist – let alone the leading abolitionist of his generation – is a historical absurdity.