When Lysander Spooner died in 1887 he left behind a body of books, pamphlets, essays, and newspaper columns covering almost half a century. But he also left something more, at least according to reports at the time. One such example comes from the author of his primary eulogy and, in many ways, intellectual heir Benjamin Ricketson Tucker – the publisher of Liberty magazine, wherein many of Spooner’s works appeared.

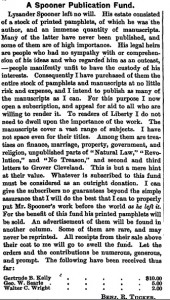

In June of 1887 Tucker purchased what he described as an “immense quantity of manuscripts” including many which have “never been published” from the Spooner estate. They reportedly included “treatises on finance, marriage, property, government, and religion” as well as unpublished parts of “Natural Law,” “Revolution,” and “No Treason” and an additional letter to Grover Cleveland.

My question & challenge, then, is where did all these papers go?

I’ll offer a partial answer insofar as I’ve found and obtained copies of two of the aforementioned treatises on finance and a handful of shorter essays that have not seen print since their composition. I also identified Spooner’s contribution to a longer article on the Dred Scott decision, mentioned by Tucker but ghostwritten and published under another’s name in 1864. It may be found at this link.

What else is out there though? Historians of the Civil War and Spooner enthusiasts alike know well his No Treason essays Nos. 1, 2, and 6, which were published in the southern periodical DeBow’s Review as a commentary upon the constitutional implications of the late war. But what happened to No Treason Nos. 3, 4, and 5? Tucker suggests they at one point existed and were in his possession. As the following notice in Liberty indicates, he also solicited funds to place them into print (the very first donor also being early feminist writer and physician Gertrude B. Kelly).

Readers who are familiar with Benjamin Tucker will also quickly point out that a large portion of his collection and most of his printing material was lost in a 1908 fire in his “Unique Book Shop” in New York City. This raises the possibility that the aforementioned materials were destroyed at this time. But a fairly large collection of Spooner’s letters did survive the fire, eventually making their way to the New York Historical Society. Also as I mention above, some of these materials did survive including the two financial treatises I’ve found, along with some shorter essays. There are also hints of additional Spooner material waiting to be found in Tucker’s papers and elsewhere.

Do you have a lead of your own on this subject? If so, I remain on the hunt for relevant materials, with an intention of making them available in print for scholarly examination and evaluation. With an intellectual progeny ranging from Frederick Douglass to Gerrit Smith to Tucker to Murray Rothbard, Roderick Long, and Randy Barnett, Lysander Spooner remains a fundamentally interesting and important figure in a distinctly American strain of classical liberal thought. Please contact me at pmagness (at) ihs.gmu.edu if you know of any untapped sources or leads and would like to share them for scholarly dissemination.

And since this is a Spooner project, a competitive currency tip jar for sustaining the hunt for documents is available if you are so inclined.