Earlier this week Paul Krugman ventured into the history of economic thought as part of his longstanding blog crusade against Austrian business cycle theory. The post presents Krugman’s own truncated synopsis of another anonymous blogger’s not particularly dispassionate summary of what an incomplete review of the secondary literature has to say on Ludwig von Mises’ early reactions to the Great Depression as it unfolded in 1930. You can read the pieces and judge for yourself at the links above, but the gist of it according to Krugman:

A caricatured Mises allegedly believed that “unemployment is high because we’re being too nice to the unemployed” or, as Krugman puts it, “soup kitchens caused the Great Depression.”

The reader of course is expected to recognize such an assessment as “crazy talk” since, obviously, the ‘victims’ of a depression cannot possibly be it’s cause. I’ll leave it to the economists to elucidate on other pressing matters of accuracy in Krugman’s portrayal of Anonymous Blogger’s portrayal of a partial secondary lit review portrayal of Mises’s actual position in 1930. But the implication, according to Paul, is that Austrian business cycle theory – in allegedly offering such an obviously crazy explanation – may accordingly be discarded, leaving us instead to accept the depression orthodoxy found in John Maynard Keynes.

Now Keynes is a complex figure in his own right, but since all is fair in love and war…and presumably politics…it might come as some surprise to Professor Krugman that his own beau ideal of an economist offered up more than a few helpings of “crazy talk” when developing his own explanations for problems in the labor market.

A choice example in this genre comes from Keynes circa 1922, who seemed to think he had figured out this quintessential ‘problem’ of the labor market. His identified cause of low wages and, presumably with it, unemployment: too many babies.

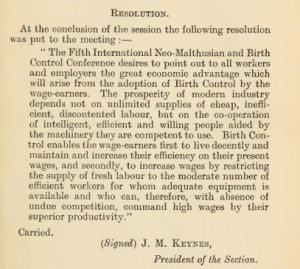

At the time Keynes was the president of the “economics section” of something called the “Fifth International Neo-Malthusian Birth Control Conference,” a quasi-academic gathering of the eugenicist New Generation League of Great Britain. Following a series of, as the conference subject suggests, neo-Malthusian papers on population control, Lord Keynes offered up an odd little resolution wherein he attributed a variety of economic ills to “unlimited supplies of cheap, inefficient, discontented labour.” The solution, he posited, was to restrict the supply of labor by controlling the supply of babies.

“Birth Control enables the wage-earners first to live decently and maintain and increase their efficiency on their present wages, and secondly, to increase wages by restricting the supply of fresh labour to the moderate number of efficient workers for whom adequate equipment is available and who can, therefore, with absence of undue competition, command high wages by their superior productivity.”

Or to convert that to Krugman-speak: Sound familiar? It should — it is, essentially, the current Republican (and labor union) story on immigration.

Nor was this oddball foray into population control as a means of “fixing” the labor market a fleeting fancy for Keynes. He returned to the subject at many points in his long and illustrious career, adding in from time to time a touch of the other less economically inclined “sections” that joined him at the 1922 Fifth International Neo-Malthusian Birth Control Conference. To that end, the following piece of “crazy talk” is highly symptomatic:

“My third example concerns population. The time has already come when each country needs a considered national policy about what size of population, whether larger or smaller than at the present or the same, is most expedient. And having settled this policy, we must take steps to carry it into operation. The time may arrive a little later when the community as a whole must pay attention to the innate quality as well as to the mere numbers of its future members.” – J.M. Keynes, “The End of Laissez Faire,” in Essays in Persuasion (1931), p. 319