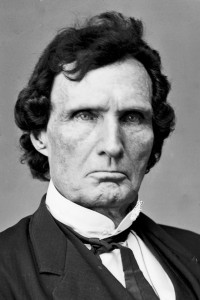

Last Saturday marked the 150th anniversary of the day the 13th Amendment passed the House of Representatives, securing its submission to the states for ratification. This momentous event – marking the abolition of slavery in the United States – has received increased attention in light of the Civil War sesquicentennial, as well as its 2012 dramatization in Stephen Spielberg’s Oscar-winning film Lincoln. Pennsylvania Congressman Thaddeus Stevens played a central role in the amendment’s adoption, and has seen his historical reputation revived in recent years on this count as well as his longtime commitment to abolitionism and equal rights for blacks.

Stevens was involved in another far less known event on January 31, 1865 though, as he also spent a part of this day meeting James Mitchell to discuss the revival of limited congressional support for the Lincoln administration’s longstanding policy of black colonization.

Mitchell is a central figure in my co-authored book Colonization After Emancipation. He was a long time colonization agent in the Midwest and acquaintance of Abraham Lincoln for about a decade before the Civil War. In 1862, Lincoln brought Mitchell to Washington and appointed him to oversee the administration’s nascent program of financing the voluntarily colonization of freed African-Americans in the Caribbean and tropical regions of Central America.

Lincoln’s colonization program suffered a setback in July of 1864 when Congress attached a rider to a much-needed budget bill that effectively repealed some $600,000 in previously allocated funding. While John Hay famously referenced this repeal in his diary as the moment that Lincoln allegedly “sloughed off” colonization, the actual story is more complex. According to another contemporary report by Mitchell, Lincoln was aware of the anti-colonization rider and described the amendment to him as “unfriendly,” though he could not afford to veto the entire budget bill on that account.

Mitchell’s loss of his budget also triggered a new stage in a long-festering feud between him and Secretary of the Interior John P. Usher. Armed with the new legislation, Usher suspended Mitchell’s salary and attempted to have him removed from his post. This initiated several months of legal wrangling that eventually reached the president’s desk for resolution. Though little-recognized even in the colonization literature, Lincoln actually endorsed Mitchell’s petition to have his salary reinstated and asked Attorney General Edward Bates to provide a legal opinion that would allow him to keep the colonization commissioner on board (noted here in the Attorney General’s logbook for September 9, 1864). Bates answered in the affirmative on November 30, 1864 and Mitchell was subsequently paid through the end of the year, though the informal opinion was tendered on Bates’ own last day in office and left the continuation of Mitchell’s position unresolved. This set the stage for the events of January 31, 1865 with Stevens.

Thaddeus Stevens and Colonization

Thaddeus Stevens had a complex and existent, albeit at times lukewarm, relationship with colonization. Some of his earliest abolitionist forays involved the formative Pennsylvania colonization movement in the 1830s. Though he greatly prioritized emancipation over colonization, he was not conceptually opposed to the latter at the outset of the Civil War. In fact, a key part of the 1862 legislation that funded Lincoln’s colonization program was inserted into the bill by none other than Stevens, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee. Lincoln sent Mitchell to meet with Stevens about the project on July 2, 1862. During the conversation, Stevens consented to the president’s proposal and asked for a statement outlining the desired appropriation. The following day then-Secretary of the Interior Caleb B. Smith formally requested “an appropriation of a half million or more dollars, to be repaid to the Treasury out of confiscated property, to be used at the discretion of the President in securing the right of colonization of said persons made free, and in the payment of the necessary expenses of removal thereto” (original letter is in Smith’s papers at the Huntington Library). Stevens then inserted the request directly into the bill.

Stevens had misgivings about the appropriation after it was announced that Lincoln intended to settle a colony in the Chiriqui region of modern-day Panama under the auspices of Ambrose Thompson. “I moved the appropriation of half a million for general colonization purposes, but never thought new and independent colonies were to be planted,” he wrote to Salmon Chase on August 25, 1862. Rather he had intended it to subsidize colonization transit to Liberia, Haiti and other locales that were already associated with black emigration.

January 31, 1865 – Colonization Revived?

Despite his opposition to Thompson’s Chiriqui project, the evidence is strong that Stevens was not yet ready to completely close the book on colonization. Mitchell’s legal case in late 1864 set the stage for its reentry into the legislative discussion, which incidentally happened on the day that the 13th amendment passed Congress.

The legal issues involved in Mitchell’s dispute were complex and remained unresolved at the time of Lincoln’s assassination. While Congress repealed the $600,000 in direct colonization funding from 1862 ($100,000 allocated in the District of Columbia Emancipation Act and $500,000 in the additional legislation secured by Stevens in July), the 1864 repeal did not apply to a third colonization funding source that remained legally in effect. A separate 1862 law authorizing the Treasury Department to confiscate and sale certain lands that were used in support of the rebellion also stipulated that one fourth of these proceeds would be allocated to support the colonization of freed slaves from the state of the confiscation. While funds from this source do not appear to have been used as specified, the Treasury Department did maintain a partial accounting of their accrual through some point in 1864, which would have potentially placed them at Mitchell’s disposal. To make matters even more complicated, the legislative debate surrounding the anti-colonization rider strongly suggested that the measure’s purpose did not envision the suspension of Mitchell’s office, as Congress had requested the delivery of his annual report for 1864 after this point.

Mitchell met with Lincoln at the White House at some point in late 1864 – likely November or December based on the context of his description – to discuss another wrinkle in the colonization venture. The Confederate government was considering a plan at the time to arm its own slaves in a last ditch effort to change the tide of the war. As Mitchell recounted, Lincoln suggested “closing the policy…for the time being” on account of “the attempt of the men of Richmond to arm and emancipate their negroes,” thus challenging the administration’s own emancipation and black soldier recruitment policy and potentially prolonging the war. This reference of the issue of black soldiers is interesting in itself, as it has commonly been supposed by a number of historians that colonization was rendered moot, or at least rendered intellectually inconsistent, by the Emancipation Proclamation’s arming of the freed slaves some two years prior. This supposed inconsistency is actually something of a modern invention though. Even die-hard colonizationists like Mitchell also supported the arming of the freed slaves, as is attested in this July 1864 letter to Lincoln outlining a scheme to raise a unit of black troops from the border state of Kentucky.

The adoption of the new 13th Amendment however had settled the matter of emancipation, and the Confederate proposal to arm their own slaves was mired in its own controversy caused by the vocal resistance of white supremacists in the Confederate Congress. With the political circumstances of the war now clear, Mitchell continued in a letter to Lincoln dated the day after the amendment: “as the question of emancipation is decided…I respectfully recommend that we cling to our outlines of a policy in regard to voluntary emigration and the concentration of the freed men in proper localities,” the latter an apparent reference to a number of domestic freedmen’s settlements and resettlement ventures that had long been coupled with various colonizationist enterprises. In particular, Mitchell was undoubtedly aware of the free black Sea Island communities that had set up in along the Carolina coast in the wake of wartime displacement. He also knew of and may have supported another domestic black resettlement scheme in Texas that was being championed at the time by Kansas’ Radical Republican Sen. Jim Lane.

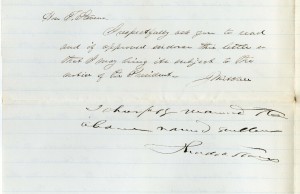

Reviving these policies had their own complications though due to the partially unresolved matter of colonization funding. Mitchell therefore ventured over to capitol hill on January 31, 1865 where he met with Thaddeus Stevens. During their meeting Stevens requested “a note stating the estimates that should be allowed on my account, as Congress had no design in cutting off the office by the repeal of the two large appropriations” the previous summer. Mitchell returned with the following note the next day, appended to his letter outlining their agreement on the partial restoration of colonization funding:

Stevens signed below. The endorsement reads “I cheerfully recommend the above named settlement.”

Congress took no further action on the proposal, and it fell by the wayside along with Mitchell’s still-pending case after the assassination of Lincoln two months later. As of February 1865 though, the case for a limited revival of congressional support for colonization appeared to have had credible backing from Stevens. Lemuel D. Evans, a displaced Unionist from Texas who had also worked with Stevens on the original 1862 colonization bill, recounted a separate conversation to this effect in a reminiscence he published in 1869.

In a conversation dated to February 1865, Evans asked Stevens “what would be the policy of the administration towards the South after its suppression.” Evans records Stevens’ answer:

“He expressed himself doubtful as to the propriety of combining the white and colored elements in one government, and said that he had not made up his judgment, as to whether it was best to leave the freedmen as they were dispersed through the South, with a view of afterwards combining thorn as an element in the governments of that section, or whether it was best to localize them in distinct communities, and in this connection, spoke of South Carolina, Florida, and Texas as proper territory for such an object.”

Evans’ statement comes with the hindsight of his own Reconstruction era conservatism, yet interestingly it suggests that Stevens still exhibited a fair amount of indecision about the future of race relations after the 13th amendment. It also describes his openness to some of the very same policies hinted at in Mitchell’s February 1, 1865 letter, bearing the endorsement above.

Stevens famously came to embrace a course of black political empowerment during the year after Lincoln’s death, and seems to have also soured on colonization judging by his opposition to a handful of Reconstruction-era attempts to revive the scheme. But as this episode from February 1865 shows us, even the history of well known events such as the adoption of the 13th Amendment is complicated by the uncertainties of the moment – including, in Stevens’ case, a final entertaining of a policy that he is commonly supposed to have considered at odds with his own post-slavery vision.