A little under three years ago I posted a brief comment about some stats I was compiling for an article on the higher ed workforce. The post investigated a myth that was popular at the time and remains so today, namely that adjunct employment had grown to encompass an astounding 76% of the higher ed workforce. The claim is empirically false on its face, and rests upon the conflation of adjunct, or part-time, faculty with all non-tenure track appointments. It nonetheless serviced a popular political slogan, suggesting that adjuncts were the “new faculty majority” and predicting the impending “adjunctification” of higher ed.

My 2015 post cast doubt not only on this overall number, but the actual source of statistical trends. Adjunct employment had peaked in 2011 at near-parity with full time positions, but the most recent available statistics at the time – 2013 – hinted at the beginnings of a retreat in adjunct numbers. After digging a little deeper, I discovered that these trends were primarily being driven by an unnoticed source: for-profit higher ed.

For-profit institutions use an almost exclusively adjunct faculty pool. It therefore followed that as the for-profit university sector boomed between the mid 1990s and 2011, adjunct hiring would follow suit. And it did. While adjunct use certainly grew elsewhere in this period, the single biggest contributor to the sector’s growth was for-profit higher ed. But in 2015, the for-profit sector was undergoing a contraction that has only intensified since then.

So I made a prediction.

Not only were we already past the adjunct workforce peak, but I further predicted that the total number of adjunct professors would continue to shrink in the wake of the for-profit contraction.

This prediction and my other stats work quickly drew the ire of a cadre of adjunct union activists who were entirely uninterested in statistical analysis that ran counter to their political cause. It also prompted a particularly nasty article by Aaron Barlow of the AAUP, who falsely accused me of statistical misrepresentation. I confronted Barlow at the time about his charge, providing evidence that he was deeply mistaken. It turned out he was no more interested in an accurate or honest assessment of the stats than the adjunct activists of the twittersphere. Needless to say, my prediction was a lone voice on the subject in an activism-obsessed higher ed sector that had already concluded its error before even considering the evidence I brought to the table.

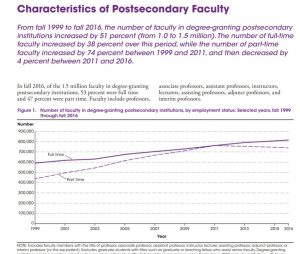

The reason I bring this up is that the U.S. Department of Education released a report last week containing its most recent set of faculty workforce statistics, covering 2016. The stats fully bear out the continued decline I predicted 3 years ago. The adjunct workforce shed 30,000 jobs between 2011 and 2016, while full time faculty positions grew by 50,000. It also just so happens that the decline in adjunct jobs directly parallels the decline in the for-profit higher ed workforce.

The AAUP would be wise to temper its activist rhetoric on the adjunct issue in light of this developing trend. For-profit higher ed has continued to contract since amidst ongoing accreditation and fiscal solvency problems, suggesting the decline will play out over several more reporting cycles.