Virginia’s desegregation fight has been a central point of contention in the ongoing controversy over Democracy in Chains. Author Nancy MacLean and several of her defenders in the historian community have attempted to depict a 1959 paper on school vouchers by Warren Nutter and James M. Buchanan as the product of an unholy alliance they allegedly struck with segregationists for the purpose of advancing libertarian education policies.

The archival evidence behind this claim is extraordinarily flimsy. MacLean both blatantly misrepresents the contents of archival material relating to this claim and confuses basic facts, figures, and newspapers in her genesis story for the Nutter-Buchanan school choice paper. But there’s also another conceptual problem with her argument: it begins with an ideologically-informed assumption that segregation and school vouchers are necessarily linked and complementary objectives.

MacLean and her defenders have often pointed to the notorious closing of Prince Edward County’s public school system in an attempt to write segregationist outcomes into the voucher proposal discussed in the Nutter-Buchanan paper. Note that she has offered no evidence that even tangentially connects Buchanan to Prince Edward County, let alone any documentation that Prince Edward school officials designed their program around Buchanan’s arguments. That has not stopped her from repeating this claim though in multiple media appearances. One of her most vocal defenders, historian John Jackson of William & Mary, has even gone so far as to suggest – also without any evidence – that Prince Edward County’s actions showed the fruits of the Buchanan-Nutter-Friedman voucher proposal in action.

Curiously, for all their speculative comments about Prince Edward County, neither MacLean nor her defenders appear to have examined what was happening closer to home in Charlottesville where Buchanan and Nutter actually lived. If they did, they would quickly discover that a pronounced tension existed locally between Charlottesville’s white-controlled public school system and the voucher concept.

The politics of the situation were complex and involved varying degrees of segregationism, including the no-compromise “massive resistance” variety offered by allies of Sen. Harry Flood Byrd, Sr. One noteworthy argument emerged out of a faction aligned with the Charlottesville school board and its ongoing legal battles with the NAACP. The school board’s attorney was John S. Battle, Jr.* the son of a former governor of Virginia and committed segregationist with close ties to the Byrd machine. *[Correction: an earlier version identified the attorney as his father, the former governor]

On March 23, 1959 – a little over a week before Nutter and Buchanan released their paper to the public – Battle addressed a PTA meeting at a local Charlottesville high school to discuss the pending NAACP litigation and the legislative turmoil over desegregation. Battle made an interesting argument intended for the committed segregationists in the audience. If any sizable portion of the white population removed their children from public schools and placed them in private schools (as could happen under a voucher-like program), the result would be to suddenly open up a mass of seats in majority-white public schools. These empty seats, Battle argued, would then be “engulfed” by a court-backed influx of black students who would force an immediate and unstoppable integration upon the public school system. If this happened, he warned, the school district would be rendered powerless to fight integration any further in the courts or legislature.

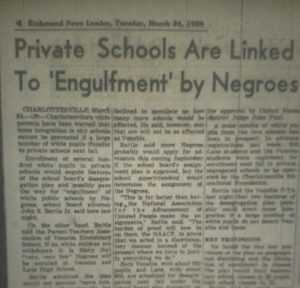

The avowedly segregationist Richmond News-Leader reported favorably on Battle’s arguments, a copy of which is displayed above. Private schools, its reporter declared, were a pathway to the Charlottesville public school system’s “engulfment by Negroes.” As Battle argued in his plea to white parents, “very few Negroes” would enroll if they held firm and kept white children in the public school system while the anti-integration fight continued.

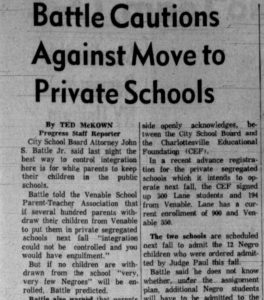

The local Charlottesville Daily Progress covered the story as well:

Further into the article, they summarize Battle as saying “that parents who put their children in tuition-grant supported private schools might find themselves in a situation where those schools would be forced to accept Negro applicants.” Instead, he urged parents to support a geographical assignment plan that would “not entirely prevent integration” but was designed to “keep integration to a bare minimum.” Quoting Battle’s speech directly:

“No Negro child is going to force any white child out of his desk at Venable [Elementary School]…But for every white child who vacates his desk there is a great risk that a Negro child will occupy it.”

So as it turns out, the local situation in Charlottesville is a much more pertinent context for Nutter and Buchanan’s paper than unfounded speculations about a link to Prince Edward County across the state. And as we can see from Battle’s remarks, given only days before the Buchanan-Nutter paper’s public release, a number of white supremacists in the city’s public school bureaucracy interpreted private school vouchers as a direct threat to their own segregationist order.

Addendum:

Two quick points to further contextualize the historical events above.

First, and with no small stroke of irony, Battle’s anti-voucher arguments can be explained through a little standard public choice analysis. He opposed vouchers as a threat to the segregationist order for the same reason that Milton Friedman advocated them – they break into the public school system’s educational monopoly and break up a number of entry and exit barriers that ensure that system’s continuation and funding. Segregation was one such barrier, and would in time find itself undermined by educational competition as Friedman liked to point out.

MacLean and her defenders have been prone to dismiss this line of argument as naive and ideological. Yet as we’ve seen above it is actually MacLean who has a tenuous and politically-distorted grasp on the circumstances of the desegregation fight in 1959. Battle’s line of attack, interestingly enough, is essentially a segregationist twist on an old argument put forth by political scientist Albert O. Hirschman in his classic (and mostly critical) analysis of school choice. Exercise of the exit option (i.e. taking the voucher) has a secondary effect of removing voice-exercising parents from the old school and thereby altering pressures upon it to be voice-responsive. Only in this case the effects are flipped. Battle is talking about removing the segregation-conscious parents from a public school, which he believed to be an important preventative buffer against that school becoming more integrated. Absent those parents to agitate for and preserve it, segregation in the public school system begins to decline rapidly…which isn’t a claim that segregation’s fall would be complication-free; only that there may be something to Friedman’s arguments after all that segregationists themselves also realized and feared.

Second, the voucher-segregation argument is actually empirically testable. Corey DeAngelis summarizes the evidence over at Cato and, sure enough, the academic literature on voucher systems in the U.S. overwhelmingly suggests that they have a real-world effect of increasing racial integration and diversity in affected schools.