As part of my ongoing investigation into early 20th century tax policy, I recently compiled a data series to track patterns in charitable giving during the 1920s and 1930s. As a result of tax code changes in 1917, the IRS began allowing federal income tax payers to deduct up to 15% of their taxable income for donations to recognized philanthropic causes. Eligible donations included charities for the poor, as well as certain contributions to the arts, scientific study, and education. The policy was intended to incentivize private giving and its successor program persists to the present day in the form of tax deductible donations to eligible non-profit organizations.

The IRS required tax filers to report their charitable deductions on their tax forms and tabulated the total amounts in their annual report on the income tax system. Surprisingly, little work has been done with the resulting data series on annual charitable contributions in this period.

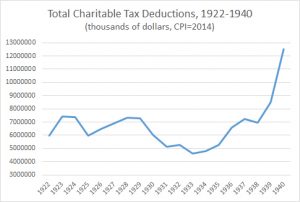

The chart above illustrates the total amount (inflation-adjusted) of charitable contributions in the period between the implementation of the deductions policy and the eve of World War II. Several patterns are noticeable. First, the Great Depression caused a precipitous decline in charitable giving that persisted into the late 1930s. While this effect is partially attributable to the economic decline caused by the Depression, its persistence also attests to the documented ‘crowding out’ effect that New Deal era spending had upon private charities. Earlier work by Jonathan Gruber and Daniel Hungerman noticed a similar drop-off in church-based charitable giving during the New Deal era, as the federal government picked up the tab for Depression-relief programs.

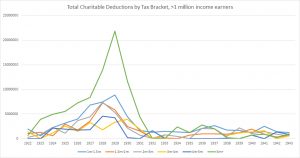

Further evidence of this phenomenon may be seen in the raw IRS figures showing where charitable deductions came from. The chart below depicts earners in the $1 million+ income tax bracket, extended through the middle of World War II. Notice several patterns. A sharp spike in charitable giving followed the introduction of charitable giving exemptions, indicating the incentive structure worked. Giving among the wealthiest Americans also spiked dramatically after the 1924 tax cut, reducing high World War I-era rates to a top marginal rate of 25%. Charitable giving among the wealthy dropped off though during the New Deal, and especially following another income tax hike enacted by Herbert Hoover in 1932. It never really recovered until some point after World War II.

Now compare this second chart to the first, depicting overall charitable giving. While donations by the wealthy are evident in the mid 1920s on this chart as well, something else is missing. The total amount of deductions actually began to accelerate around 1939-1940 in the first chart. This acceleration occurred even though deduction patterns for the wealthiest earners remained essentially flat during the same years.

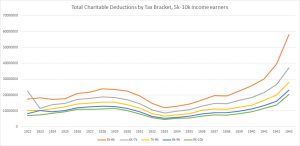

What explains this somewhat counter-intuitive pattern? The answer may be seen in the next chart, showing raw charitable deduction amounts claimed by lower level income earners – specifically tax brackets for incomes between $5,000 and $10,000 per year (note: an almost identical pattern appears for earners in tax brackets below the $5,000 mark, although IRS records did not report these brackets individually in most years – only in cumulative).

As we can see in this chart, donations from the bottom of the income ladder actually drove the spike in charitable giving in the early 1940s. The reason has to do with yet another set of changes to the federal tax code. Beginning on the eve of the war and continuing until 1945, Congress rapidly expanded the federal tax base onto lower income earners and simultaneously increased income tax enforcement to control for tax evaders. This was done in part to finance the war, though it also involved major administrative reforms such as the addition of automatic payroll withholding in 1943 to increase tax compliance. Faced with a newfound tax burden, lower income individuals began taking advantage of the same charitable deduction allowance that the wealthy utilized to alleviate their own tax burdens in the 1920s.