Just over two weeks ago, Berkeley economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman approached the New York Times and Washington Post with an astonishing claim. According to new calculations performed by the pair, the wealthiest earners in the United States paid an overall effective tax rate in 2018 that was lower than the bottom half of the income distribution. The claim plays a central role in Saez and Zucman’s newly released book, The Triumph of Injustice (hereafter referred to as SZ-2019).

The claim went viral on the progressive end of the political spectrum and quickly became a talking point of the Elizabeth Warren campaign, which Saez and Zucman also advise. But there was also something fishy about their new numbers. While SZ-2019 produced a flashy chart that purported to show the top 400 earners’ tax rate dipping below the bottom half, this pattern also broke sharply from their own previous published work including a 2018 article with Thomas Piketty in the top-ranked Quarterly Journal of Economics (hereafter referred to as PSZ-2018).

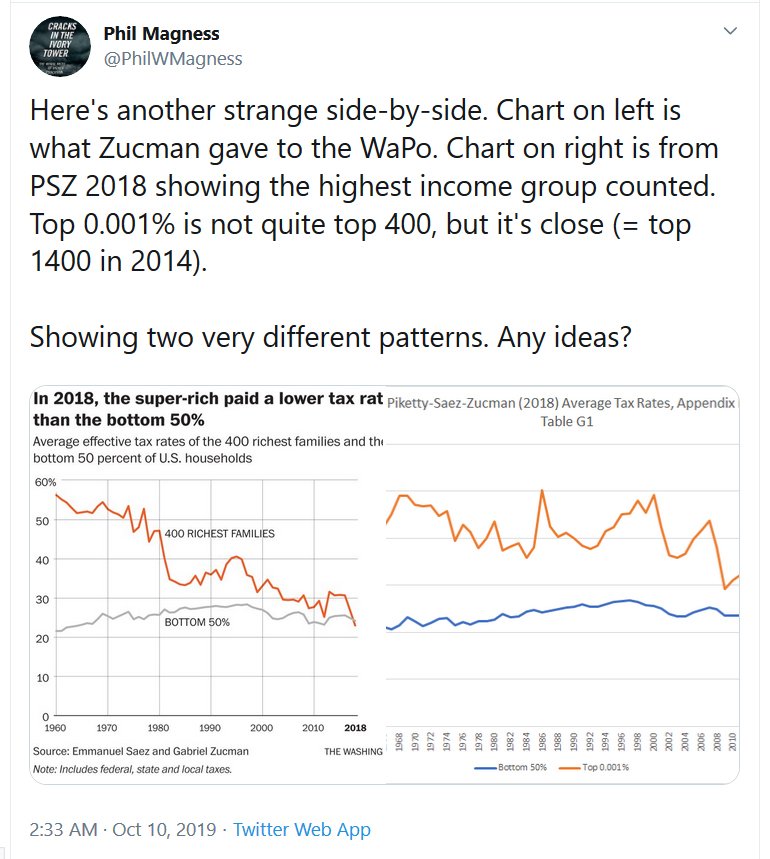

In a chance discovery on October 10th, I noticed something odd about the new chart from PS-2019 when compared to the paper from last year. PSZ-2018 did not directly measure the tax rate of the top 400 earners, but it came very close by offering an alternative measure of the top 0.001%. It looked nothing like the new results though. Instead of a sharp decline in the tax rate of the ultra-wealthy over time, the PSZ-2018 numbers showed a relatively flat pattern that only fluctuated year-to-year. For example, the top 0.001% average tax rate in 1962 was 44%. In 2014 it had only changed 3 percentage points, sitting at 41%.

So I tweeted an open inquiry about the discrepancy.

Several other economists took notice of similar discrepancies, and were able to tease out further oddities about the SZ-2019 data. For example, Saez and Zucman appeared to be intentionally removing the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) from their estimations for the lowest tax earners. This is an extremely unconventional move that contradicts over 40 years of standard practices by the Congressional Budget Office and similar tax statistic agencies in the U.S. government. The EITC is intended to increase the progressivity of the federal tax system, and omitting it creates the illusion that the poorest tax filers pay a higher rate than they actually incur after the credit is incorporated.

The bigger discrepancies, however, were at the top of the distribution where Saez and Zucman now showed a sharp decline in tax rates over the past 40 years. When pressed on twitter about this oddity and its inconsistency with his prior work, Zucman was generally evasive. He responded to substantive questions about his stats with flippant dismissals, name-calling, and even blocking users who challenged his findings. The discrepancies would be explained, he promised, in a forthcoming data release on October 14th – timed with the official release of his book.

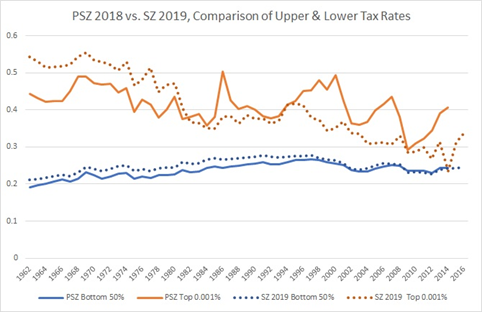

The promised release date arrived and it became apparent what had changed between PSZ-2018 and PS-2019. Columbia University economist Wojtek Kopczuk posted a helpful deconstruction of the two charts. Saez and Zucman had dramatically altered their previous assumptions about how to assign and distribute corporate tax incidence across the top earners. The change was highly technical, and their new assumptions contradicted decades of scholarly literature on how to handle corporate tax incidence (I discuss it in detail here). But the big takeaway is that the new assumptions in SZ-2019 completely altered the results that they published in PSZ-2018, producing the downward shift in top tax rates. A comparison of the changes may be seen below:

As can be seen, SZ-2019 yields dramatically different results than PSZ-2018. But that was not the only oddity about Zucman’s new data release.

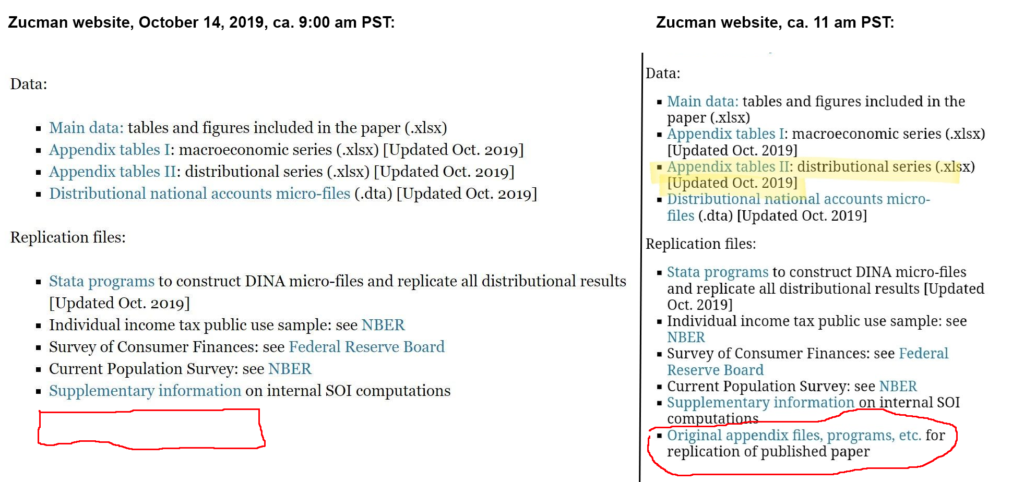

When Zucman posted the promised data files from SZ-2019 on a new website made specifically for the book, he also initially removed the old online data appendix to the published QJE version of PSZ-2018 from his personal website. He then replaced that file with a “new” version of the PSZ-2018 appendix that conveniently matched the newly released SZ-2019 numbers.

Zucman defended his actions by claiming that the new file constituted an “update” to improve the accuracy of PSZ-2018. Updates to published works, however, normally come from small data refinements. This one involved a major change to the underlying assumptions of the published paper’s methods. Unlike the published version, those changes had not undergone peer review – and likely would not survive it, seeing as the new corporate tax incidence assumptions break sharply from the established literature.

The oddities in Zucman’s behavior only expanded from there, as Kopczuk noticed the newly replaced file for PSZ-2018 lacked any indication that it had been changed from the older published version of the article. Zucman insisted it was only a misunderstanding, and that the old file had simply been moved and relabeled at another place on his website and pointed Kopczuk to that section. Yet something was still off about the data release.

Within minutes, several other economists began reporting that they had noticed the same thing – the old PSZ-2018 files had been replaced without any indication of what happened to the old file. One of them, Jeremy Horpedahl, shared a screen capture of Zucman’s website from about 2 hours earlier showing that the old PSZ-2018 file was clearly missing after being “updated” with the SZ-2019 numbers. Zucman apparently restored the old file to his website sometime after he started to come under criticism for removing it. A side-by-side comparison may be found below:

We may only speculate at this point what Zucman’s intentions entailed. At best, it involved a sloppy roll-out that only added further confusion to the SZ-2019 data release and accompanying questions about its unconventional methods.

That botched roll-out contrasts sharply with a slick marketing campaign behind the book, which included advance releases of its data to friendly reporters at the New York Times and Washington Post, who ran stories promoting their findings as “facts” before the new book had even been subjected to academic scrutiny. While the new Saez-Zucman numbers are still being processed and scrutinized, it has already become apparent that they represent an outlier finding when compared to other work on the same subject. This has not stopped the Warren campaign and friendly pundits from using the SZ-2019 data to advance their own arguments on behalf of wealth taxation.

But there’s also a more fundamental question of scholarly transparency at play. Rather than going through normal channels of academic peer review and commentary, Saez and Zucman have packaged their latest statistics for a media release in conjunction with a presidential campaign. The scholarly side of their project has taken a clear back seat to its use for electioneering purposes. Perhaps the aforementioned oddities of the data release only reflect sloppiness that arose inadvertently from this inversion of priorities. But it’s also becoming a pattern with the new SZ-2019 tax statistics that calls their objectivity and credibility into question.