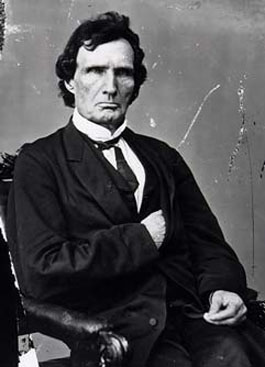

Thaddeus Stevens has enjoyed something of an academic as well as popular revival in recent years, becoming known as something of an archetype of that all-too-rare character in mid 19th century American politics: a racial egalitarian.

He was also an abolitionist of some note and, most famously, the de facto leader of the radicals in the Republican Party. But was he, like Abraham Lincoln and many other figures who subscribed to a distinctly more moderate flavor of antislavery, a colonizationist?

Perhaps with surprise to some, the evidence points to yes. But like many colonizationists in a movement if wide and changing motives, his support was of a nuanced variety.

Historians have long known that Stevens was involved with colonization in the sometimes-fluid circles of the Pennsylvania antislavery movement in the 1820s and 30s. His Civil War years are less well known even among his primary biographers, some of whom simply assume that he must have been hostile to the idea of voluntary but subsidized black resettlement.

Yet Stevens lent his support to the Lincoln administration’s colonization program, even going so far as to author the enabling legislation. Specifically, he appears to have personally attached colonization funding to the 1862 budget bill, which in turn permitted the colonization clause of the Second Confiscation Act – also known as the law that authorized the Emancipation Proclamation.

The train evidence begins in a letter on July 3, 1862 from James Mitchell, the main colonization agent in the Lincoln White House. As Mitchell informed the president:

I have had interviews with Hon T Stevens Chairman of the Committee of Ways and Means and several Senators and Representatives in regard to an appropriation for the relief of such of the Contrabands as may desire to emigrate. Mr Stevens requested me to ask at your hands a short message, recommending this appropriation so as to aid its passage — he states that he has a bill nearly ready on which he can place the sum and asks that the recommend be sent on as soon as you can find time to make it. (Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress)

The requested letter arrived on Stevens’ desk the same day, written by Caleb Smith, the Secretary of the Interior under whose department the colonization enterprise fell. The relevant excerpt reads:

To enable the President to carry out the Act of Congress for the Emancipation of the Slaves in the District of Columbia, and to colonize those to be made free by the probable passage of the Confiscation Bill, I respectfully suggest an appropriation of a half million or more dollars, to be repaid to the Treasury out of confiscated property, to be used at the discretion of the President in securing the right of colonization of said persons made free, and in the payment of the necessary expenses of removal thereto. (SS 366, Spooner-Smith Papers, Huntington Library)

Notice how Smith’s text mirrors the Sundry Civil Expense Bill, passed a little over a week later and revealing that Stevens was indeed the

To enable the President to carry out the Act of Congress for the Emancipation of the Slaves in the District of Columbia, and to colonize those to be made free by the probable passage of the Confiscation Bill, five hundred thousand dollars, to be repaid to the Treasury out of confiscated property, to be used at the discretion of the President in securing the right of colonization of said persons made free, and in the payment of the necessary expenses of removal.

This in turn funded the colonization clause of the Second Confiscation Act later in the month:

And be it further enacted, That the President of the United States is hereby authorized to make provision for the transportation, colonization, and settlement, in some tropical country beyond the limits of the United States, of such persons of the African race, made free by the provisions of this act, as may be willing to emigrate, having first obtained the consent of the government of said country to their protection and settlement within the same, with all the rights and privileges of freemen.

Stevens seems to have maintained a nuanced though by no means hostile view of the colonization enterprise from there on out. He groused in a letter to Salmon Chase a month later when Lincoln announced an intent to use the funding on a project in modern day Panama, though this likely had more to do with Stevens’ distaste for the particular location and the scheme’s organizer Ambrose W. Thompson. He considered the country “so unhealthy as to be wholly uninhabitable,” suspected the validity of Thompson’s land title, and accused him of corruption. Stevens’ own preference was probably for Liberia. As he explained to Chase, “I moved the appropriation of half a million for general colonisation purposes, but never thought new and independent colonies were to be planted. I intended it in sending aid to Hayti Liberia, and other places…”

Stevens would later declare in an 1864 speech that he had “never favored colonization except as a means of introducing civilization into Africa” though even this did not signal his abandonment of the concept. On February 1, 1865 – the day after the 13th amendment passed – Stevens also offered his support for the partial restoration of the colonization fund, which had been rescinded by a Senate measure the previous summer. His endorsement on a proposal by Mitchell to reestablish the colonization office on a more limited basis read “I cheerfully recommend the above named settlement.” A visitor during the same month affirmed as much, reporting that Stevens told him “that he had not made up his judgment, as to whether to leave the freedmen as they were dispersed throughout the South…or whether it was best to localize them into distinct communities,” including the possibility of domestic colonization proposals on tracts of unsettled southern lands. In any case, to Stevens in the final days of the Civil War, a resumed scheme of colonization was still very much within the realm of consideration.