At risk of venturing into political philosophy, I have to admit my intrigue with an ongoing dialogue between David Friedman and a group of commentators for the always-insightful Bleeding Heart Libertarians blog on the question of “social justice.” As an advance warning the debate is primarily philosophical and addresses this concept in the abstract. Though the vagueness of its definition is among the currently contested points, “social justice” in this context generally concerns itself with evaluating a society on account of the care or condition of its least well-off, its poorest member or class, or some similar iteration of the concept. The debate is also couched in the presentation of this concept by the late 20th century philosopher John Rawls, or a famous criticism thereof posed by economist F.A. Hayek.

The Hayekian critique is of particular interest as it questions whether the vagueness of the concept of “social justice” renders it nonsensical on account of its social (or societal) extension effectively diffusing or voiding its attachment to a particular act of injustice against a defined subject. I’m inclined to sympathize with those who point to the lack of a robust definition for the term or its associated concepts. Though “social justice” theory is replete with expressions of concern for “the poor” or “the least well off” these terms can be carelessly utilized, are often difficult to pinpoint, and almost inherently take on a normative character. It is thus in many ways a matter of language, or more precisely whether something might be distinguished as “socially just” beyond the simple attribute of having attracted that moniker, as if conveniently plucked from a sea of vaguely defined and fluid concepts.

To be clear, it also seems that one may legitimately critique the ill-defined character of “social justice” even as he or she still holding out genuine, heartfelt sympathy for the impoverished, disadvantaged etc. But it also may sell the concept short to dismiss it out of hand on account of a deficient definition.

So where does the historian enter this admittedly abstract discussion? We do have our own “social justice” undercurrents and historiographies (to say nothing of Rawls’ own philosophical interest in Abraham Lincoln to bring it all back home – but that is for another post). But insofar as the present dialogue is concerned, I’ll offer two connected “historically” themed observations.

First, I’m inclined to question whether Hayek’s oft-paraphrased and oversimplified quip about attaching “social” to a word and rendering it nonsensical is the proper Hayekian critique of the concept to focus upon. Instead might we be better served to borrow another page from Hayek and ask “why the worst get on top” of governing regimes, insofar as it seems to intersect with the ubiquitous political use of “social justice,” past and present? In other words, is there something intrinsic to the concept of social justice – as historically and presently defined – that makes it especially attractive to “the worst” elements of the political class, or perhaps exceptionally conducive to situations wherein a stated goal of eradicating a vaguely defined and immeasurable “social injustice” facilitates the commission of many specific particular and defined acts of injustice in its pursuit?

This brings up a second observation, enlisting past applications of “social justice” as a political objective. The empiricist in me looks to the term’s many historical applications and, finding past calls for “social justice” abundant (and abundantly imprecise) as well as the concept’s use for purposes that seem to violate other and more robust conceptualizations of justice more often than not, leads me to conclude that there is something severely wanting in the way this term has been defined or understood to date.

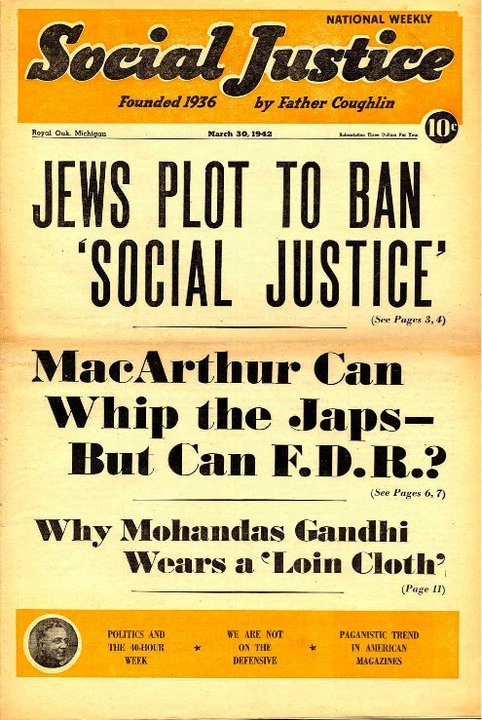

It may come with surprise to some that several non-Hitlerian iterations of fascism rank among the most vocal pre-Rawlsian claimants to a cohesive theory of “social justice,” including on terms of poverty-alleviation not far removed from its present form. The concept – vaguely defined as ever – was (and remains to this day) one of the central pillars of Argentinian Peronism, and particularly its left-leaning variants. In the United States, social justice provided both a platform and masthead for the inflammatory “radio priest” Charles Coughlin, a quasi-fascistic New Deal critic from the anti-capitalist but also anti-marxist left. Perhaps most notoriously, an appeal to a “higher social justice” on account of the least advantaged and laboring classes may be found throughout the speeches and political tracts of Benito Mussolini. While the road from conceptual “social justice” to authoritarian monsters of this ilk is by no means a necessary extrapolation and indeed it would be inappropriate to claim as much, it is also suggestive of a peril wherein severe and abusive political acts carried out in the claimed pursuit of this ill-defined concept, hence the applicability of Hayek’s aforementioned theory of the worst rising to positions of power through the tools and pursuit of a fundamentally societal goals at the expense of affected individuals.