The Journal of Economic Literature (JEL), a well-regarded academic journal that covers research trends and practices in the profession, published an extremely unusual and in many ways problematic review article in its September 2017 issue. It’s behind a paywall, but if you have access to the AEA website you can view it here.

The article takes the form of a 20-page broadside against Thomas C. Leonard’s recent book Illiberal Reformers, a study of the role of eugenics in the founding of the economics profession. Leonard’s book dives into an inescapably controversial subject that brings up ugly matters of pseudo-scientific racial theory and related attempts at hereditary planning that attracted a following among several distinguished founding members of the AEA. It does so with remarkable even-handedness that is meticulously sourced and has attracted widespread acclaim in the profession. For example, it received the 2017 book prize from the History of Economics Society – the main scholarly association for experts in the history of economic thought.

The JEL review is a true outlier to this pattern, and a particularly caustic one at that. Its authors – think tank economist Marshall Steinbaum and historian Bernard Weisberger – are unusual choices to write this review, particularly in a high-ranked economics journal. Neither author has much of a demonstrated expertise in the highly specialized subject matter of Leonard’s book, and in the lead author Steinbaum’s case, the review itself is actually his debut publication in a ranked economic journal. Assigning this review to two non-specialists, one of them a novice, makes for an odd editorial decision in any circumstance for an upper tier journal. Occasionally these things slip through the cracks, as journals do receive dozens or even hundreds of book submissions for review and editors are often left playing catch-up to simply cover the materials in their possession.

What troubles me more about the JEL piece though is its coupling of an aggressive attack on Leonard’s scholarship with very little substance to justify its derision. The review opens by accusing Leonard of “motivated history” and proceeds to cite him for a long list of malpractices:

“sweeping statements about what “the progressives” believed, festooned with cherry-picked quotes and out-of-context examples, without much of a hearing for either their opponents or for debate and disagreement among themselves.”

Oddly enough, the 19 or so pages that follow provide very little in the way of specific examples of where Leonard allegedly committed these scholarly sins. It simply asserts them as so. The charges are rendered doubly ironic when one realizes that co-author Steinbaum has also spent the last few months as one of the most vocal and public advocates of Nancy MacLean’s evidentiary train wreck of a book, Democracy in Chains. And triply so when considering that Steinbaum’s defense of MacLean is premised upon his acceptance of her unsupported and innuendo-laden charges of “racism” against James M. Buchanan and the public choice school of thought.

In the JEL review, Steinbaum and Weisberger attempt the opposite maneuver of trying to exonerate a group of early 20th century racist progressives from – well – their own racism, as documented in Leonard’s book. The JEL review essentially becomes a political exercise in damage control over the faults of its historical subjects.

While Leonard is careful to contextualize the eugenic and racial theories of men such as Richard T. Ely, John R. Commons, and Edward A. Ross in the academic discourse of the time where such beliefs ran rampant, Steinbaum and Weisberger approach his mere raising of this long-neglected subject as a personal affront to their own deeply progressive political beliefs in the present day. This leads them to attempt to bury the documentation Leonard uncovered in euphemism. The active eugenic campaigning by Leonard’s subjects – taking the form of lengthy published tracts on racial pseudoscience and leadership roles in eugenic organizations – thus becomes shortened to the “involvement of some progressives in eugenic advocacy” and a “blind eye toward racism” as differentiated from actual racism itself.

A few of these figures – Commons and Ross – were so inextricably wedded to white supremacist notions that they do become difficult for Steinbaum and Weisberger to ignore entirely. But that leads them to arguably the most egregious of their attacks on Leonard. On the first column of p. 1078 in the review, Steinbaum and Weisberger attempt to rehabilitate Commons and Ross from Leonard’s depiction by presenting their “exclusionary” (read: racist) views as a more benign expression than other forms of racism in their time. They are allegedly tempered by motive, as Commons and Ross supposedly used “exclusionary” arguments in the service of collective bargaining for other groups of oppressed and marginalized workers. It is not a complete clearing of their names, but it does seek to soften the problems with these progressive economists’ racial views.

Steinbaum and Weisberger contrast this comparatively restrained and worker-centric motive with a more malicious view that they assign to unspecified laissez-faire “intellectual adversaries” of progressivism from the turn of the century. The more malicious view, of course, is a racist typology rooted in control and oppression out of service to “the market.”

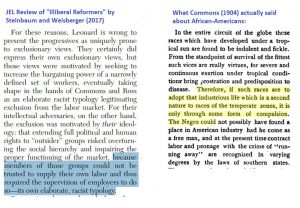

There’s a problem with Steinbaum and Weisberger’s argument though, as it not only breezes past Leonard’s evidence – it blatantly misrepresents Leonard’s findings. The side-by-side comparison below of the Steinbaum/Weisberger review and one of the racist tracts Leonard cites from John R. Commons is illustrative:

The section on the left and highlighted in blue is Steinbaum and Weisberger’s description of the racism they attribute to the progressives’ laissez-faire opponents. It contrasts with the euphemism-coated depiction they offer of Commons in the sentences immediately before it.

To the right and highlighted in yellow, I present the text of John R. Commons’ 1904 essay “Racial composition of the American People,” which Leonard cites while discussing his racial views. It’s a particularly nasty passage in which Commons describes African-Americans as a genetically “indolent and fickle” race. He then proceeds to make the very same racist argument that Steinbaum and Weisberger attempt to excise from his work and assign to his adversaries. Commons asserts that the black race will only work if compelled to do so and even goes so far as to hint that slavery illustrated this principle, stopping just short of defending the institution.

This example is, unfortunately, characteristic of the remainder of Steinbaum and Weisberger’s essay. It also abuses basic historical evidence to advance an ideologically motivated sanitizing of Commons’ beliefs. It will be interesting to see what the JEL’s editors make of having such an egregious misrepresentation of evidence appear in their journal.