“What about university administrator bloat?” This question is commonly posed in conjunction with the adjunct activist movement, and usually identified as an “obvious” source for funding that could be reallocated to other purposes. And it might well be suitable for reallocation, though as Jason Brennan and I showed it is not obvious that adjuncts deserve to be first in line to receive this funding. One thing is certain though: administrative bloat is real, and it consumes an ever-growing percentage of higher education budgets.

Unfortunately, administrative budgets are not the pot of gold that many adjunct activists make them out to be. University administrators are stakeholders in the spending equation too, and far from being the “corporate” managers that are commonly depicted in the activist literature, they actually tend to behave more like government bureaucrats. As bureaucrats, their motives are not “profit” but rather budget maximization for the purpose of securing and expanding the comforts of their respective administrative fiefdoms.

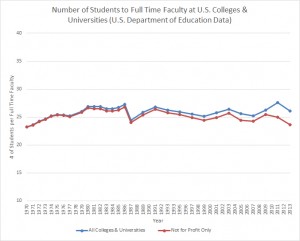

Contrary to popular claims, administrative growth has not come at the expense of full time faculty. Nor is it a cause of “adjunctification.” As I showed previously on this blog and as Jason and I demonstrated in our article, the hiring patterns of full time faculty are remarkably stable and predictable. Excluding the for-profit sector, the U.S. university system has consistently maintained a ratio of 25 enrolled students per 1 full time faculty for the past 40 years.

Adjunct growth has exploded in this same period for a number of other reasons (most recently the for-profit sector), but this ratio also makes it clear that nobody is raiding the ranks of full time faculty to prop up administrative functionaries. Faculty hiring is keeping its stable historical pace with student enrollment.

What, then, is going on with skyrocketing administrative costs? Part of the answer comes from the type of administrative growth we’ve seen over the past 40 years. Most of the rhetoric around higher ed administrative bloat focuses upon the top level, including university presidents, vice presidents, and other high ranking executives. Compensation for these jobs has increased to fairly dramatic levels in recent years, creating its own problems of waste and resource mismanagement. It isn’t the only story though, or even the largest component. The number of executive-level administrators has actually grown very slowly – including substantially slower than the ranks of full-time faculty.

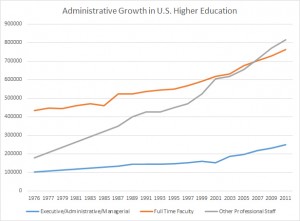

The following chart depicts administrative growth between 1976 and 2011 (the most recent year with comparable data) along with full-time faculty growth, as tracked by U.S. Department of Education IPEDS survey data. Executive and managerial level administrators are depicted in the blue line. Full-time faculty (meaning adjuncts are excluded) are depicted in red. As may be plainly seen, full time faculty growth has far outpaced executive-level administrator growth over the entire period (note: administrator data from 1976 to 1987 are interpolated).

A more interesting trend may be found in the gray line, which depicts an explosion in “other professional staff.” These categories also exclude what might be termed “support staff” – meaning everything from facilities maintenance to university dining to office secretaries (support staff numbers have remained fairly stable for at least two decades, hovering around 930,000 employees give or take). The U.S. Department of Education defines the two main university administrator categories as follows:

Executive/administrative/managerial – Employees whose assignments require management of the institution or of a customarily recognized department or subdivision thereof. These employees perform work that is directly related to management policies or general business operations and that requires them to exercise discretion and independent judgment.

Other professional – Employees who perform academic support, student service, and institutional support and who need either a degree at the bachelor’s or higher level or experience of such kind and amount as to provide a comparable background.

Administrative bloat, it would therefore seem, is primarily a product of rapid growth in the second category, or the lower levels of the university administrative bureaucracy. While the Department of Education unfortunately did not break down these functions on a line item basis, they are defined as including most university jobs that require a bachelor’s degree or higher. The ranks of these lower level campus bureaucrats have exploded in recent decades and show no signs of slowing down. And while they are not acquiring their funding at the expense of the still-growing ranks of faculty, they are gobbling up university resources at a frightening pace.

Some of this administrative bloat is to be expected. One likely source is the creep of regulatory mandates from the Department of Education and those accompanying state and federal student loan programs. Accreditation review, which largely determines access to federal student loans and research money, has also become a more laborious process with the passing of time. While there is almost certainly room for efficiency improvements in these areas, they encompass functions that are at least plausibly considered essential. As mandates and reporting requirements increase over time, universities will likely require additional staff to simply keep their institutions in compliance with regulatory mandates and to retain accreditation with a recognized accrediting body.

But what about the other low-level administrative functions? My hunch is that they reflect the worst tendencies of the budget-maximizing bureaucrat. Here it is not difficult to see how university presidents or governing bodies acquiesce to student, faculty, and staff pressures to provide funding for a wide variety of pet causes, which then morph into permanent bureaucracies. In this vein, we’ve witnessed a relatively recent explosion of “green sustainability” offices – university bureaucracies that receive hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars to reduce the campus “carbon footprint.” Or recall the “safe space” protester movement that swept several campuses over the fall and winter of 2015-16. While premised on student debt relief and calls to combat racial injustices, many of the lists of protest demands actually included additional funding to be allocated to any number of student counseling, student life, student diversity, and student “justice” offices – all functionaries of the administrative bureaucracy’s lower levels, and almost all of them perfectly willing to receive those investments.

I personally happen to believe that many of these “pet cause” administrative offices are little more than wasteful captures of university resources, and misappropriations of student fees and tuition dollars. They also raise distinct questions of justice on their own. For example, is it “just” to raise tuition on students in order to fund an ideologically charged administrative office that promotes environmentalism on campus? I would argue that “sustainability” offices are not just on two grounds: (1) they allocate student-derived funding to a primarily political cause that not all students willingly support and (2) they take money from a comparatively vulnerable and underemployed economic group – students – and use it to provide comfortable employment for mid-career bureaucrats who are, generally speaking, on much sounder economic footing. But there may be many other areas of university spending where we should be asking similar questions.

In any case, the problem of administrative bloat also highlights the reality of trade-offs in university budgeting. Let’s suppose for the moment that, yes, all adjuncts “deserve” more money than they currently receive and that money may be found by simply reallocating it from administration. Consider the following questions, some of which have more obvious answers than others. In order to fund the adjuncts:

- Are you willing to reduce administrative functions that are charged with ensuring federal regulatory compliance, or conducting institutional review for accreditation purposes?

- Are you willing to cut student life and student recreation offices, which tend to provide perks that attract new students to enroll?

- Are you willing to close down the campus writing center, or other similar non-teaching curricular support offices?

- Are you willing to cut back on campus IT services?

- Are you willing to eliminate student counseling services?

- Are you willing to defund the professional staff in all of those deanlet offices that support student clubs, student government, and student activism?

- Are you willing to shutter the Office of Diversity and Inclusion?

- Are you willing to scale back the financial aid office? Or the admissions office?

- Are you willing to cut community engagement functions? Or cut campus life functionaries who support cultural and artistic endeavors?

- Are you willing to give up your campus’ effort to become “carbon neutral” by the year 2030, and close down its Sustainability Office

All of these things and more have administrative functions to them that fall under the very same lower level administrative staff that caused almost the entirety of the same administrative growth you bemoan on the whole and tout as a source of funding to be reclaimed.

We might also ask the following: what do you plan to do with the administrative staff in university fundraising and development? Their ranks have grown too and, generally speaking, they are net revenue producers. It might be worth mentioning at this point that many of the madjunct ideological devotees attack the revenue that the development office brings in when they dislike (or harbor conspiratorial prejudices about) the private-sector source, even when it goes toward hiring more faculty. In any case, cutting development staff – a part of the gray line, for the most part – would likely cause the actual loss of funding.

As with most aspects of the university system, it’s more complicated than the shallow presentations found in the activist, public, and media discourse about higher ed.

Note that I am not disputing the presence of waste in these areas, and quite the contrary. I suspect that it is abundant, and I suspect that universities could survive and thrive while scaling back many of these functions and even eliminating a few of them. That said, knowing the commonly expressed preferences of university faculty at large and adjunct union activists in particular, I also suspect many of the most obvious areas I might target for cuts are also areas that they strongly support retaining (any madjunct volunteers want to lead the charge to close ineffective and politicized writing centers? How about eliminating spending on all the silly carbon footprint reduction initiatives?).

So yes, we should cut administrative bloat. And we should have a discussion about where its funding should be reallocated, whether it means more pay for part time faculty or lower tuition for students or a refund for taxpayers or something else entirely. But in order to have that discussion, we also need to recognize that there will be trade-offs involved – including trade-offs that many nominal advocates of administrative reform will be less-than-eager to make once they move beyond activist slogans about fighting “badmin” and into the weeds of deciding what is actually being spent and where.