The federal revenue situation of the late 19th century United States presents a somewhat case study in constitutional political economy, owing to a fairly restrictive constitutional restraint on the means of raising revenue for the federal government. The U.S. Constitution provided Congress with the “Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises” as its primary means of taxation, yet it also provided that “No Capitation, or other direct, Tax shall be laid, unless in Proportion to the Census or Enumeration herein before directed to be taken.”

Taken together, these clauses bestowed a de facto constitutional primacy upon the three types of specified taxes of the first clause: “duties, imposts, and excises.” While other types of direct taxation were technically possible, the proportionality stipulation tied to the census made them politically and administratively unfeasible. This left Congress with essentially three main sources of revenue in the 19th century: tariffs on foreign imports (collected under the impost provision), duties and excises on domestic goods (mostly in the form of liquor and tobacco excise taxes), and federal land sales, which greatly diminished after the middle of the century.

Owing to Civil War era precedents, there was initially some ambiguity as to whether federal taxes on income qualified as a “Capitation, or other direct, Tax.” Following a test case that attached an income tax measure to the Wilson-Gorman Tariff of 1894, the Supreme Court weighed against its constitutionality in the landmark 1895 decision Pollock v. Farmer’s Loan and Trust.

The income tax supporters consisted of multiple political factions: free traders who viewed it as a way to shed the protective tariff system, agriculture state politicians who saw it as a way to shift some of the tax burden onto the industrial northeast, prohibitionists who morally objected to revenues derived from alcohol import tariffs and domestic excise taxes, and ideological progressives – the faction most famously associated with the income tax movement, although in reality they were but a small part of an eclectic coalition. Despite the setback in Pollock, the income taxers continued to search for different ways to amend the revenue system of the federal government without running afoul of the constitution or – potentially – even forcing the Supreme Court to revisit the issue.

The outbreak of the Spanish American War in late April 1898 provided an opportunity, as wars tend to cost money and funding the United States’ imperialist venture provided a pretext to implement a wartime tax measure.

We are presently just a little over a week shy of the 116th anniversary of the War Revenue Act of 1898, and indeed the past week coincides with the little-remembered floor debate that produced its lasting legacy: the federal estate tax.

The estate tax was controversial for the time and concerns were strong that it might rub up against Pollock, though it was intentionally framed in the legislation to work around the aforementioned “capitations” clause restrictions on direct taxes. The Senate debate quickly devolved into a logrolling free-for-all cloaked in the veneer of wartime patriotism. The income taxers, pursuing an incremental strategy with the estate tax, joined forces with a group of currency manipulating bimetalists who wished to devalue the gold standard-based dollar with the mass issuance of silver certificates at a legally prescribed exchange. Together they had the votes to push the measure through despite significant opposition and – judging by prior votes in the decade – a likely defeat for both measures when taken alone and unattached to militaristic adventurism. After all, guns were needed to fortify the coasts and ships were in demand to sustain an American naval blockade of Cuba and potentially press beyond as the dictates of the war (and the politicians behind it) determined.

The 1898 estate tax imposed a graduated scale of rates ranging from 0.75% to 15%, depending on the size of an inheritance and the relationship of a recipient to the deceased (non-lineal descendants were taxed at higher rates the further removed they were from the estate).

The estate tax raised $1.2 million toward the war – a paltry amount compared to the $206 million in tariff receipts and $168 million in alcohol excises in its first year of collection. But like most war measures, it lingered around long after the cessation of hostilities and continued to grow in returns, peaking at $5 million in receipts in 1901. The “War Revenue Act” estate tax remained in place for almost a decade before finally being allowed to expire in 1907. True to expectations, it was also challenged in court in the 1900 case of Knowlton v. Moore, which, through a heavy indulgence in semantic trickery, found the estate tax to be a “duty” upon the “distributive share” of the deceased person’s estate as opposed to a direct tax upon the estate itself.

The 1898 measure’s expiration after a decade provided a brief interlude in estate taxation, though that too resumed with a vengeance under the Revenue Act of 1916 and further wartime hikes during World War I.

A related research note:

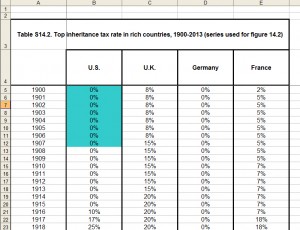

Given the subject and emphasis of my other posts over the last few days, I would be remiss if I did not point out to my readers that the War Revenue Act of 1898 and its precedent-setting estate tax measure is oddly and completely missing from the history of U.S. taxation provided by Thomas Piketty in Capital and the 21st Century. The top estate tax rate in the United States was actually 15% during its lifespan, which actually made it the highest such rate among the four countries he considers at the outset of the 20th century. Yet Piketty records these years as 0% for the United States. So once again, his historical data is shown to be erroneous and deficient.